The first and last time I saw the Mehrangarh Fort at Jodhpur and the bright blue houses that surround it, it was from a distance..from on top of a three-storied building of an acquaintance who lived in the city back in 2007. So, as I braced for take-off from the New Delhi Airport for Fabindia’s FAM trip to Jodhpur with colleagues from the fraternity, I wondered if the famous opening line from the book that my seatmate was reading (Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier) — Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again — had any bearing on the trip we were about to have. Would much have changed in Jodhpur since the time I was last there, 11 years ago? Well, it certainly had. The city that once barely showed any signs of globalisation now had Subway and Domino’s Pizza outlets and not many of its women hid behind the ghunghats of their traditional Marwari clothing. Modernity had taken over, but the Mehrangarh Fort still loomed large against the skyline of pink sandstone buildings, just like the scene from my memory.

A quick ten-minute drive and we are at our destination for the night — The Karni Bhawan. The erstwhile home of the former Jagirdars (feudal landlords) of Sodawas Bhati Rajputs of Lunar Dynasty, the heritage structure was built in 1940. Initially, a colonial bungalow that was built of red sandstone, the building was refurbished into a heritage hotel with 12 rooms in 1986. Currently hosting guests in 31 rooms, each suite in the hotel was designed to recreate the ambience of the cities in Rajasthan. We wearily trudge up the stairs to our rooms on the third floor on an unusually humid afternoon and I notice my fellow travellers quickly disappear into the Udaipur and Bikaner suites that are right next to the stairwell. Mine, however, is at the end of the corridor — Room 403: The Jaisalmer Suite. The irony of the situation hits me as I sink into my double-bed that is decked up with Sangeneri block printed bed sheets: I had lived in Jaisalmer years ago and a wave of nostalgia comes rushing in.

Something old

Lending an aura of regality the antique wooden furniture, cupboards and pictures that adorn this haveli-styled building does add to its colonial ambience, but the dim-lighting within the heritage structure that has housed British royalty like Prince Charles is a letdown. “No selfies for us!” I think as I slip out of my room and head to the terrace hoping to once again catch a glimpse of the Mehrangarh Fort against an almost setting sun. Instead, I am received by a vantage view of the Umaid Bhawan Palace. Imagine if you will, a panorama of one of the bastions of Rajput heritage set against a cloudless blue sky as dusk falls and the palace lights flicker on. A spectacular sight and suddenly we’re no longer complaining about the dim lights. My reverie is broken by a phone call from our Fabindia host Shreya telling me that our ride to Mehrangarh is here.

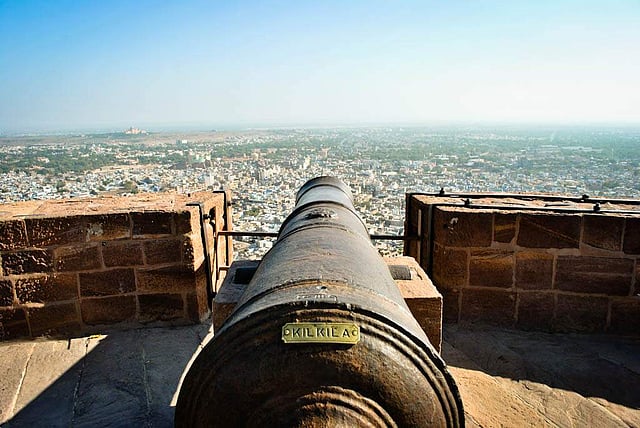

Built by Rao Jodha who laid its foundation in 1460, the fort is surrounded by the old city that lends Jodhpur the title of the Blue City. Our guide tells us that the rooftops of the houses were painted blue to keep them cool from the inside during the desert summer. “...blue is considered a sacred hue in this region.” trails off another guide leading a group of foreign tourists. Smiling sheepishly our guide at the fort confirms that there are multiple theories behind the name and one can never be too sure. “Maybe, the famous indigo textile has something to do with the name,” adds Shreya.

Something blue

While the locals have their own lore about the title of the Blue City, one tale that everyone agrees on is that Jodhpur’s other title as the Sun City and that of Mehrangarh, which translates into House of the Sun, is in reference to the myth that the Jodhpur royal family are Suryavanshis (descendants of the Sun god). This palatial hill fort stands at an elevation of 420-feet above the city and has a series of seven gates. Consisting of the Sheesh Mahal (hall of mirrors), Phul Mahal (palace of flowers) and Moti Mahal (house of pearls), the museum fort today houses paintings, textiles and armoury, showcases the region’s craftsmanship and puts on display the Rajput alliance with Mughals through its architecture that makes extensive use of jaali and wall carvings. Memorialising the macabre event of Sati committed by the 30 ranis of Maharaja Man Singh in 1843, a set of red handprints belonging to each of the queens is found on a wall beside the final gate of the fort, the Loha Pol (embedded with iron spikes to prevent elephant attacks).

This grim reminder of the past does dampen the spirits of our all-girl contingent, but we quickly realise that there is nothing that some hot pyaaz ki kachori, laal maas and Rajasthani tawa rotis can’t cure. Soon we find ourselves discussing the movie The Dark Knight (portions of which were shot at Mehrangarh), Salman Khan and his connection to the city and block printing over a traditional Rajasthani spread, each of us wondering who should have the last piece of the melt-in-mouth mutton that is prepared with yoghurt and red Mathania chillies.

Block party

Early the next morning we’re already out on the road and army contingents on their morning drill line the route leading out of Jodhpur. Our destination is 60 km away and it’s 7 am by the time we reach Pipar city. Reams of indigo fabric lie drying on the ground within the premises of what seems like a museum for carved wooden blocks. We are at the workshop of the last surviving block printers in the region — the Shahabuddin brothers, who specialise in indigo dyeing and dabu block printing. Third generation master craftsmen, the family that has been in the trade for the last 200 years and now controls the monopoly of blockprinted indigo textile from the region for homegrown brands was identified by Fabindia owner William Bissel over 20 years ago. “My father never wanted us to continue in this trade but, here we are,” laughs Farooq Shahabuddin, the youngest of the three brothers, as workers in his factory scurry around to get to their workstations for the day’s work. Once a colour that symbolised colonial oppression, indigo is now a favourite of fashion brands across the world.

Though drawing in part from the bagru printing of Jaipur, Pipar’s block prints are characterised by the use of the resist-dyeing dabu process that has its roots in the region. The dabu paste is created using a mixture of mud, wheat, gum, calcium and limestone which is filtered through a sieve leaving a thick, smooth mud paste. Using special dabu blocks that have deeper grooves and wider lines printers then stamp mud patterns on the fabric, we learn. Unfazed by our peering eyes, the hands of these artisans swiftly align the blocks perfectly to create repeat patterns on pristine white fabric. The rhythm and precision with which these blocks are placed on the cloth is almost hypnotic. “Sawdust is gently sprinkled over the mud to prevent smudging, preserving the natural beauty of the mud print,” explains Farooq. Once dry, the fabric is then steeped in the family’s heirloom indigo well or pot-dyed in other colours like red, black or yellow. After dyeing, washers rinse the mud off the fabric, revealing white coloured patterns where the mud was protecting the cloth from the dye. “Like stars in an indigo sky,” he says with a laugh.

Prints charming

Known for their deep indigo shades and double indigo patterns, Farooq is quick to give credit to the 30-year-old indigo water in a 15-foot-pool. “The water has never been changed. Every batch of indigo fabric is dyed in this pool. We just keep adding indigo paste as per requirement.” Importing indigo from Machlipatnam in Andhra Pradesh, the Yasin family does not use any artificial dyes and creates all its other colours in-house. In fact, Farooq tells us that his older brother Mohammed Yasin was initially identified as an indigo block printer by the blue stains on his hands from repeated exposure.

A labour intensive craft, a single sari takes upto15 days to complete. The final design, in most cases, is a combination of multiple patterns and motifs — each having a different colour, we notice. Catering majorly to one of the largest retail chain stores in the country that specialises in products that are made from traditional techniques, skills and hand-based processes, a considerable amount of design directive in terms of block print patterns are provided by Fabindia. “Geometric prints are currently in trend and a large number of prints are dedicated to the pattern. Traditional jaal (connecting designs) designs which were formulated under Persian influence, lehriya (wave) and kanguras (triangles) are also all-time favourites,” shares Farooq , referring to the collection that will soon hit stores.

Something new

Keen to partake in the dyeing process from the heritage indigo vat, my pick for the dabu block print is a floral motif along with the lehriya design on a white piece of cloth. Three dips in the dye and a fast-tracked drying session later, we head back for our hotel with blue fingers clutching onto our indigo pieces of history. The last image as I buckle up for our car ride to the airport is once again of the Mehrangarh fort — pink sandstone and all. But this time I decide a mental panorama won’t do. “I might not dream of its skyline again,” I tell myself as the shutter snaps shut on my phone.

Dabu silk cotton sari at Rs 4,990.

From the source

Working with Chanderi cotton and silks and Kota cotton and silks among other yardages, the block printers at Pipar source their fabrics from weaving centres across the country.

DIY colour

Black hack: Iron scraps in addition to jaggery, tamarind seed powder and water that is left to ferment for a period of 20 days.

Red spread: A mixture of alum, water and tamarind seed powder that is boiled until thick and left for 10 days.

Did you know

While synthetic dyes are colourfast, easier to make and can be reproduced onto nylon and polyester, block prints from natural dyes can only be produced on natural fabrics.

The fabric steeped in indigo comes out of the vat looking green. It turns the familiar blue as soon it is oxidised by the sun.

(The writer visited Jodhpur and Pipar on invitation by Fabindia ahead of the launch of their Indigo Collection)