- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

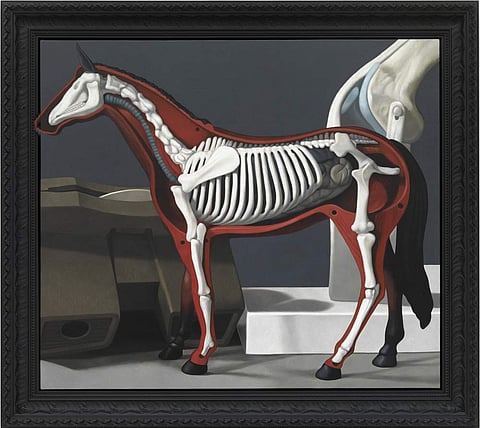

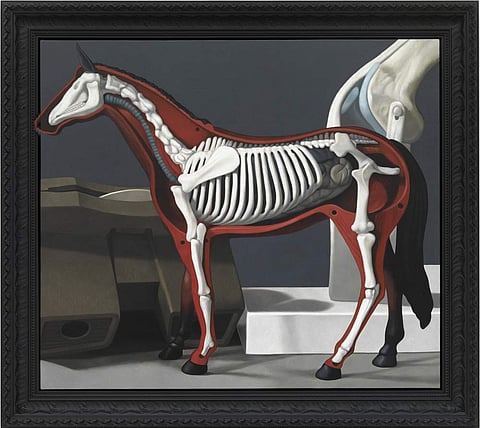

It has been a landmark year for Thai artist Natee Utarit, even as he’s being hailed for his wildly subversive artworks and installations that question everything from religious beliefs and social structures to ethical and moral persuasions about capitalism and a global culture. Importantly, Natee’s work reveals the power of contemporary art, as a potent medium that can create a genuinely meaningful and positive impact on people.

The idea of a willing suspension of disbelief, of disregarding reality and logic for something dreamlike and enjoyable, is the primary impulse that grips you, as you begin browsing through the paintings of Thai artist Natee Utarit. We were first introduced to Natee, who’s represented by the gallery Richard Koh Fine Art in Kuala Lumpur, at the India Art Fair held in January, in New Delhi, earlier this year.

At the time, Natee had just released his hugely influential collection, Optimism is Ridiculous: The Altarpieces, following up with a more elaborate presentation extending the prevailing theme, Optimism is Ridiculous: Paintings on Figure of Speech, Paradoxes and Inward Journey in April. In June, Natee went on to show View from the Tower, his first solo in Bangkok after 11 years, before going on to host the exhibition Untitled Poems Of Théodore Rousseau in October. He also saw the launch of the book, Natee Utarit: Optimism is Ridiculous, edited by Italian curator and art critic Demetrio Paparoni.

To be sure, even as Natee is being hailed in art circles around the globe, his ideas are resolutely subversive and decidedly post-9/11 in context. Concerns over the commodification of religion and the commercialisation of art fuel his works, as do matters of colonialism and imperialism, and the constant interplay between European and Asian ideologies, and their evident disintegration in this technology-driven age.

In the simplest terms, Natee questions the construct of God, in the present day; his works frequently cite tributes and existentialist quotes by Friedrich Nietzsche, Voltaire (‘If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him’ says one canvas), and Jean Paul-Sartre (‘l’enfer, c’est les autres’ or ‘hell is other people’). On a personal level, however, Natee remains an avowed Buddhist.

In essence, Natee’s works convey a load of anti-establishment sentiments, taking to statements such as ‘innocence is overrated’ or ‘money can’t buy friends, but it can get you a better class of enemy’. But he’s also careful not to come across as overtly sacrilegious, and consciously avoids all profanity.

For an aesthetic overview, Natee’s works might seem like modern-day Hieronymus Bosch polyptychs, given their elaborately complex nature, rife with progressive and often deliberately provocative ideas. Some might even say, Natee’s ideas are not for the faint-hearted, not when he’s prone to dissect the divinities under a cultural microscope, and reduce generations of social mores and mannerisms to mere posturing and pithy platitudes.

Yet, at a time when contemporary art itself finds itself under question — for its motives and purpose, its constructs and limitations — the art of Natee Utarit gains importance, as a mirror to the possibilities that art presents today, not just for thought, but for actual social change. In that sense, Natee might well be on the cusp of a revolution — one that’s slowly rearing its head, and gearing up to be acknowledged in a larger manner — as he plays the figurehead of another immensely impactful and politically driven art movement, much like Chinese contemporary artist and activist, Ai Weiwei.

In an email interaction, Natee spoke about his formative ideas, warming up to concepts of globalised acculturation, and paving the path for a meaningful creative process.

The idea, ‘Optimism is Ridiculous’: How did you arrive at this assertion? And how relevant is the idea to current affairs?

‘Optimism is ridiculous’ reflects affairs of the present day, especially those happening in my country — and with my region — ever since the post-colonial period.

I like the sentence: Optimism is ridiculous.

Sarcastic as it may sound, the sentence quite obviously evinces attitudes towards what happened. I myself don’t have a problem with optimism. But then again, an optimistic or one-sided viewpoint can cause you far more problems than just being ridiculous.

Certainly, it concerns not only the relationship between one’s self and one’s perception of the outer world, but also the relationship between one’s self and one’s perception of the inner world. As for my work, the sentence embraces my attitudes towards obscurities in social, cultural and religious beliefs that stem from changes since the post-colonial period.

My country (Thailand) succeeded in avoiding Western colonisation de jure, but in practice, it seems to have a greater effect that has influenced our social and cultural perspectives. My current set of paintings echo such matters via figures of speech, paradoxes and comparison, and an inward looking way, according to beliefs of Buddhism.

Are you a pessimist or a realist by nature?

In the words of Quentin Crisp, the English writer and raconteur (1908-99): “If you describe things as better than they are, you are thought a romantic. If you describe things as worse than they are, you are thought a realist. If you describe things as exactly as they are, then you are thought a satirist.”

For a recent show, I called one of my paintings, The man who is a pessimist before 48 knows too much; if he is an optimist after, he knows too little. The canvas shows a fox staring at its own reflection in a mirror. I am very fond of this sentiment. It expresses something that is very true.

I am now 48 years old. I consider myself to be an existentialist and a pessimist. My philosophical beliefs were shaken for a while when it seemed to me that the only existentialists in the 21st century were tired old conservatives who were never satisfied with anything — people unhappy with a world of rapidly changing social and cultural conditions — a world where we seem to have so many more choices than in the past.

Sometimes, I have the distinct impression that I know too many things, but just as often I feel as if I don’t know anything at all. But then maybe there isn’t really much difference between knowing and not knowing. After all, knowing too much makes it hard for us to face the truth. It changes our perspective on the world around us, and as a result, what we value and find meaningful in life changes, too.

I’m always asking the people around me if we aren’t looking at things too optimistically. Is everything we see really as beautiful as it seems? These kinds of questions aren’t meant to destroy people’s faith; they are a reflection of our uncertainty and loss of belief in the reality right there in front of us.

We can’t deny that always looking at life through rose-coloured glasses doesn’t teach us much of anything about how to live our lives in the world as it is today — a world where reality is so much more intense and so radically different from the past.

Give us an idea of how you combine mediums in your creations: of connecting painting with photography and classical Western art. How did these mediums come together for you?

I started painting in 1994. It’s the only medium I’m interested in and use for expressing my ideas since. The ‘image’ has been my cup of tea since my early years. Hence, no other media is more suitable for communication than painting.

I have also used photographic images for my creation. In our time, we cannot talk about painting and photograph separately. We cannot separate sculpture from material as well.

I grew up in the period of photography, which has developed to digital photography, and a world of images at present. It’s beyond imagination, in my opinion, how we have leaped to the current world of photographs and images, in less than 20 years.

I always keep that in mind when working. I usually find new image materials that I’ve never used for creative expansion. I used all kind of materials unconditionally to keep my identity. My models come from real people and things I’ve owned. I use images and many interesting characters from print media that I’ve stored.

I also create images using computer graphic technology, in case I need sufficient information about an architecture model. When I developed my interest in Altarpieces in an attempt to send out questions about beliefs and post-colonial ideas, I did more research on Western painting especially.

How important is the act of subversion for your artistic process?

I am interested in ‘deconstruction’, because it leads to inner and outer self-analysis. I don’t think there’s ‘newness’ in art anymore. Everything has been sought-after and created through hundreds of years of ‘art development’.

What exists are ‘new angles of interpretation’ under different attitudes and contexts. In my paintings, I often start with ‘Why’ and ‘How’ questions, which help shape the content as well as my method of creation.

I’m interested in artistic ideas that question everything around and challenge existing ideas ‘smartly and ‘politely’. But I will not draw the audience’s attention with aggressive moves. How can it be possible to ask for a sense of refinement and delicacy, as well as concentration of the mind, if you have to grab the audience by the collar or use vulgarity?

I’ve been very careful about this. We cannot use ‘art’ as an excuse for any violation or misleading act, as in, artistic pieces crafted to specifically challenge or overthrow existing ideas. There are sensitive issues in society and many should be questioned. The ‘How’ question is necessary to create a balance between content and artistic presentation.

Would you agree that all art is inherently political by nature? Do you believe it is possible to make art that is non-political?

Art emerges from an attempt to find recording and communication channels. We can’t deny the existence of politics and it becomes the essence that drives people’s lives and ideas.

It makes no difference from the mythology that influences lives, ways of thinking and all kinds of art creation. I don’t think we can ignore politics because it surrounds us in various conditions, especially at present.

Politics is an advantage-laden relationship. Citing this, it covers a wide range of affairs from the small ones between two to social, national and governmental levels. Politics can be found anywhere – workplaces, the sports world and the art world. Such politics is describable once we realise their relationship with advantages and resource allocation. It does not seem unusual.

For me, I have lived in a society with political conflicts for a very long time. From then to now, conflict roots have stretched increasingly further to even smaller units in the society. It becomes an influencer of my ideas. I use politics as the first premise to interpret things under my worldview and attitudes.

At present, political contradiction and its implications are no longer in my work, since finishing Illustration of the Crisis in 2012. Politics is still influential material in my ideas with differences in context, interpretation and meanings. For me, refusal of political opinion is another way of politics.

There are so many reasons around in the world today to be unhappy. We’re keen to learn about your ideas of channelising strong emotions such as anger, frustration and outrage into art.

I’m enthused by negative and gloomy feelings from news and public incidents, as well as people’s emotions on Facebook.

Subjects of art once used to be about beauty only. But once art expands to include other possibilities, there is a wider space for other emotions including rage, aggression, and depression — all consequences of the era. Things happen without warnings. It’s like the elementary school shootings in the US. These incidents reflect the emotional and spiritual crises of our vice-indulging time.

Art’s mission is to perceive what becomes of the world, and present it via a creator’s attitudes. Contemporary art has raised issues, encouraging audiences to think and look back at more individualistic questions. Art is a creative process, and it exists for human ideas and spirits to gain more insightful perceptions of the world.

We're interested particularly in the discussion about serious, intellectual content in contemporary art. A lot of work today is still meant to please the senses, and therefore, we find a general tendency to reduce the significance of art with a message. Give us your thoughts about art making a genuine difference, and actually moving people to think, and perhaps, act differently?

I think it is the turn of new era. Art represents a specific era, and it varies by society. What happens in social media is merely another form of the contemporary art process. An ultimate identical will and need, as far as I’ve seen. 70% of Facebook and Instagram content are for self-distinction rather than communication.

I don’t go in for social media. I have paid no attention to it and try not to have problems with it. I admire thought-provoking, idea-stimulating pieces. I don’t like those trying to grab your attention within three or four valuable seconds – that’s all each piece has at art fairs.

Art should not be just for the attention of one audience. Art in the early days was to spiritually serve and spread faith and belief from religion and philosophy to personal belief. They were made to serve our faiths toward specific things. Created by faith, such pieces certainly contained stories and the self of the creator. Big or small, in a single sentence or more than that, they are full of intelligence to be passed on.

I am very satisfied seeing an audience considerably look at art pieces, spending their time with them. Time today seems to be quicker that that of yore, though time movement is physically the same. I feel like time around me has changed. Only art can make it stop and give you time to spend in your own world.

Music and literature as well. We don't have the songs with long, refined, thought-provoking lyrics like those of Bob Dylan anymore. Unlike memorable and inspirational guitar solos in the 1970s, what we’ve got nowadays are synthesised sound from drum 'n’ bass and short, easy-to-remember lyrics that take you nowhere.

Everything seems to be in the same direction. A large number of people begin to long for lost values and return more to old-fashion art as well as archaeological stuff with a historical background, showing faith and honesty to what they have done. I’m among those seeking the missing values in contemporary art.

At what point would you draw the line between being a reactionary or rebel or dissentient and the idea of being a thought-provoking contemporary artist? Are there occasions when you have to caution yourself, and take extra care just to be on guard, about the lines that you might be crossing, and the things that you might be saying? How wary are you of censorship?

Art itself has the mission to accomplish – presenting happenings in the epoch. As contemporary artists, our responsibilities for such things remain. Actually, there are many things in society that we cannot talk about directly. We might, if we try, but it might be deemed inappropriate.

Art has become a necessary tool for the mission since the old days. There are various ‘ways’ to express a sentence to obtain a totally different outcome. One could make it the most vulgar, highly refined, shallow, obvious or cleverly covered. We use these for assessing whether the presented message is impressive. Smart communication methods via a visual language is called ‘art’.

Look around and you will find art in well-thought, well-managed pieces under a clear will and with impressive results, such as in culinary arts, or oration, etc. Thoughtless, vulgar-speaking people will not be regarded as orators.

I think it’s the same thing that we have discussed. Painting has a wide range of solutions to such problems for centuries, and I’ve learned from them. I’ve never been worried about my message, I don’t have to do self-censorship. All I have to do is thinking of art exquisitely.

Tell us about your deep-seated interest in symbolism - how do you see so many of these objects losing their older meanings, and gaining new definitions and significance, in the new age? How much of your art is actually about semiotics, and the study of signs and symbols? In that sense, what would you say, your art is symbolic of?

I developed my interest in symbolism and metaphors while finding my way to represent domestic politics via my paintings in 2006. I found symbolism had been used in paintings, containing various stories and contexts. Christian art and Oriental art also employ symbolism.

A symbol is an arbitration of connecting things to give meanings to another. So it needs mutual understanding and conditions. Besides, symbolism in art does not work the same way as traffic signs. It’s not that flat and limited. Symbolism in art is more flexible and more related to context.

I think the use of symbols for meaningful connections and figures of speech define a smart visual language. I use a wide range of semiological methodology in my paintings: universal symbols, my own symbols and very specific symbols. All will be re-arranged and re-contexualised for accurate communication.

For that reason, I don’t think my paintings should be categorised as symbolism. I adopt symbols simply because I need them. Symbols, for me, are like footnotes to the sentence I coined; I use them only when necessary.

As an artist, do you enjoy a sense of chaos, confusion, conflict and contradiction? Are you more inclined to disrupt things, or would you rather be content with nature? Give us some insight into your process of making art, and conceptualising images that you produce.

I love diversity as well as order in disorder, because I’m inevitably a part of such diversity and confusion. Globalised acculturation such as in Bangkok seems to bring in equality, but it also spurs us to be awake to our true selves and express our own cultural identities.

Apple and Facebook, under a fleeting glimpse, seem to loosen up differences and confusion but they, on a more profound level, conceal increasing contradictions, and self- and social conflicts. This is the actual chaos and confusion. My works lately often show such chaos and confusion, especially in The Altarpieces.

I think we could perceive and feel chaos and confusion in the paintings easier than what we did in our environment. Maybe because we get used to them. As for questions about my art-creating process, it is rather complicated, with a splendid array of pre-production work. I’m afraid, I might not be able to describe them all here – content, painting prototypes, models, costumes, materials in the work and the painting process.

Tell us about the artists who have inspired you, over the years. Also, among contemporary artists, whose work really excites you? Are there any Indian artists whose work you're interested in?

I’ve been inspired by many artists whom I have faith in, and in their works, varying over my working period. My interest varies from Giotto (di Bondone) in the Late Middle Ages to contemporary artists. My latest inspiration is Fra Angelico. I hold Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke in high regard for their contemporary work and artists of our century.

Among Indian artists, I admire Anish Kapoor’s 1000 Names. Despite being made in the 1990s, it provides inspiration related to the foundation of faith in the sense of contemporariness magnificently. I also admire the work of Bhakti Kher.

Is there an idea here about a unified global religion — one which takes in the good and bad of all other belief systems? Is contemporary art the new religion of progressive minds?

I found that all beliefs of the West and the world changed after 9/11. They were severely shaken. Questions about God and his existence and scientific progress proceeded rapidly in the reverse direction.

Contradictions between belief and the current state of being, expectations and occurrence, faith and proof, all lead us to the picture of one throwing a giant rock into serene waters. Such chaos happens on Earth in every region, at different ratios and contexts.

I think there’s an obvious change — some realise happiness in their remaining lives; as the future is unpredictable. When sought after, at the fullest, it’s all about individual happiness. Many people have left no stone unturned, reaching out for new faith to re-enhance their spiritual strength.

There are more atheists. And most just realise the uncertainty of the future, unlike they have ever felt before. It’s a scene from my point of view.

Art (and contemporary art) are mere movements under global change. Art itself is not a core factor to change human beings’ beliefs and thoughts. It’s like a wave on a surface of water — the rise and fall before a new wave reaches.

Contemporary art is not a stone tossed into the river. It is simply a tidal wave of all changes. To create more possibilities, more stones need to be thrown for the surface waves to move further. Or there might be no more waves.

That is my guess: Optimism is Ridiculous.

For updates on Natee Utarit’s shows or to request copies of the book Optimism is Ridiculous, contact Richard Koh Fine Art on their website or Facebook page.

— Jaideep Sen

jaideep@newindianexpress.com

@senstays