- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

Hope is that silver lining on the darkest cloud, they say. For the art community, hope manifested itself as the mega art exhibition, Lokame Tharavadu, which is currently showing at Alappuzha, Kerala. When the pandemic first reached our shores and caught us all unawares, the world around us crumbled; businesses collapsed, hospitals filled up with people gasping for breath.

As artists, though we work within the confines of our private spaces, art does need a platform and an audience. With galleries and exhibition spaces shut indefinitely, a return to normalcy in the near future looked bleak. We continued producing art nevertheless... art that echoed our fears and our angst, all the while clinging on desperately to the fast disappearing traces of hope, that the world would heal soon.

Mission possible

One man though, had a vision, a grand one at that, in the midst of this crisis. Bose Krishnamachari — the internationally acclaimed artist, curator and co-founder of the Kochi Muziris Biennale, which is the largest art exhibition in the country, — not just dreamt of a large-scale exhibition with 140 artists who trace their roots to Kerala, but went about planning it, while most of us, still reeling under the impact of the first wave would have thought it to be merely a pipe dream. With this ambitious plan in mind, he went from Mumbai — where he resided — to Kerala, at a time when no one stepped out, let alone travelled.

When each of us artists received a call from him, inviting us to not only participate but to treat it as our solo show and present several of our works, it was almost like that fast disappearing hope had reappeared miraculously. Not stopping with that, Bose set out, travelling the length and breadth of the state, visiting studios, meeting artists, discovering new talent and all the while, adding to the earlier list of 140 artists, until it became one of the most inclusive shows to have ever happened in Kerala.

Organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation with the support of the Kerala government, this mammoth show slowly began to shape up. Needless to say, the excitement among the artists was almost contagious. “When Bose first called me and proposed this show that would be a revival of sorts of the very successful Double Enders, a show where he had brought together 69 artists from Kerala, I was completely in support of the plan. With the pandemic raging, Bose’s personal visit to artists’ studios really mattered and created a feeling of optimism in the art community” says Delhi-based Gigi Scaria.

Bose himself was stunned by the immense talent he encountered during these studio visits. “I found some incredible artists, young and old, often in the interiors, with tiny studios or working from home. I could not resist adding to my list”, says Bose. The list of participating artists soon swelled to a whopping 267, as he relentlessly travelled across Kerala. As much as it sounds like a cakewalk, it certainly would have been a frightening prospect for most of us, safely ensconced in our homes. “Bose’s drive is unmatched. It takes a certain level of dedication and passion to not just think of such an ambitious project but to actually go out there and do it, even risking his health. If only every state in our country had a Bose,” says Vivek Vilasini, a participating artist.

Calm amid crisis

Just as with all projects of this scale, monetary support is key. As the opening dates neared and with funds running short, the challenges faced seemed insurmountable, but Bose remained confident. Seeking help from patrons and artists, and chipping in with his own money too, he managed to clean and convert dilapidated warehouses and old heritage buildings into international level exhibition spaces, in time for the show. Spread out over seven large venues in the picturesque port city of Alappuzha — often called the Venice of the East, for its canals and backwaters — the spectacular show finally opened on April 18 and the mood among us artists was nothing short of jubilant.

Unfortunately, this exuberance was short-lived. No one expected the second wave to cripple us so badly, and so soon. With the imposition of the second lockdown and barely two weeks after opening, the exhibition had to temporarily shut its doors to the public. A sense of dejection set in, as the participating artists had been working for months, and awaited the show. But there’s something about the human spirit, which often resurrects in the face of an adversity. It was that spirit that bounced back with rekindled hope, when the organising team conducted a series of online panel discussions, where participating artists could talk about their practice and discuss the idea of home and identity.

Premjish Achari, the programme and editorial head of Lokame Tharavadu recalls, “When Bose had asked me to curate certain programmes and head the editorial, physical programmes were planned as it seemed like a safe situation. But, a few weeks after I took charge, the second wave forced us to temporarily shut down. I had planned a series of conferences, seminars and talks that dealt with local history, architectural interventions, problematise the ideas of home and homelessness. We identified a wide range of experts for these talks. Furthermore, a series of cultural performances were also planned. Everything was postponed without any date of reopening the exhibition.

Therefore, the important task for me was to transform the exhibition as a space for dialogue and deliberation. Bose has provided all of us a platform through this ambitious exhibition. It was now our turn to extend the possibilities. So, I decided to launch a series of online talks and panel discussions that engage with the core theme of the show, the conditions of art pedagogy and the future of art festivals. These programmes were able to sustain the creative efforts and also gather the artist community together to provide hope in the time of distress.”

This thread of hope caressed us till the situation eased enough to reopen the exhibition after four months. Ever since, the number of visitors have been increasing and none have returned disappointed or disillusioned. Shireen Gandhy, owner of one of Mumbai’s oldest galleries, Chemould Prescott Road, who was a recent visitor to the show shares, “I feel a bit overwhelmed. Entering into Kerala through the artistic practices is such an interesting way. I feel this is a huge discovery of Kerala artists. One has to be insanely passionate to do something so outstandingly fantastic as what Bose has done. Also, the fact that each artist has been given little solo shows helps to see substantial work of each artist and get a sense of their practice.”

Artists at work

Anand Gandhi, the acclaimed film director too seemed awed by the whole experience. “In 1995, astronomer Bob Williams decided to point the Hubble Space Telescope at a patch of the sky filled with absolutely nothing significant. The telescope stared into nothingness for about a 100 hours — at a huge economic and personal risk — and soon poured in light from galaxies, billions of light-years away, fundamentally changing our understanding of the universe. For me, an intervention like Lokame Tharavadu is a similar exercise. Artists of my generation point their telescopes towards the unknown and in comes light, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of the self and the universe. I won’t be exaggerating in saying that my experience at the exhibition expanded my sense of self.”

No surprises there, at these reactions, as Kerala has always produced some of the finest artists in the country. The coming together of senior, celebrated artists with young, emerging ones is an eyeopener to the diverse culture of the state.

Gigi Scaria created four new works for this show, portraying the uncertainty of our times. ‘Stuck’, a bronze work which has a tree trapped within a home, signifies how our environment is suffocating with the mindless development of our urban spaces, while another work which shows a line of people looking up at a boulder almost falling on them, speaks of an apprehension of the future, relevant to our times.

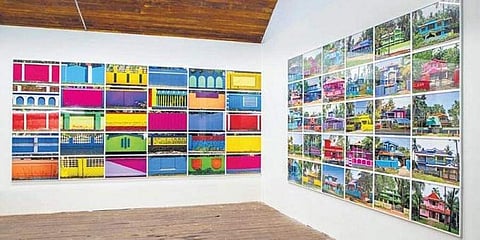

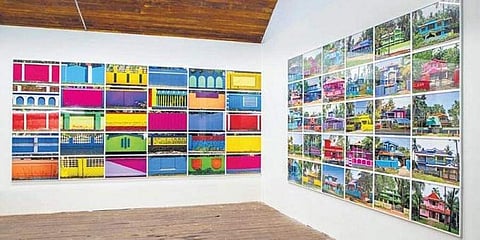

Ratheesh T’s works, which are predominantly self portraits, go beyond the self to address larger issues of caste and skin tones. Vivek Vilasini’s 30 photographs on a single canvas, captures the colourful houses one typically finds in Kerala while KL Leon’s ‘Bhojanam’ is a series of paintings of food that has come to define Kerala.

Ajayakumar’s works reflect his writings about histories as well as present-day life. TR Upendranath, a Kochi-based artist has exhibited his series of drawings, and Bara Bhaskaran has highlighted the role of women in Kerala’s historic struggles in his series titled ‘Chambers of Amazing Museum’. Delhi-based Anoop Panicker’s nine-coloured drawings of architectural and structural figures, PG Dinesh’s re-excavated sculpture series, Manoj Vyloor’s large paintings, sculptures by K Reghunadhan who was part of the Radical Movement of the 1980’s, Murali Cheeroth’s paintings that deal with social and environmental issues, Shantan Velayudhan’s drawings on paper....the list is endless with more than 3,000 artworks on display.

Beyond gender norms

Lokame Tharavadu features 56 female artists, some of whose voices have never been heard before and yet, have proved to be the strongest. Sheetal Sivaramakrishnan who has made an installation using Augmented Reality narrates, “Though each artist has an intimate and mostly isolated practice, shows like Lokame Tharavadu helped create a collective space that provided a semblance of normalcy during the pandemic.” Hima Hariharan, a new mother, spoke of the positive energy she felt when she was invited to participate.

Through their powerful works, these female artists have opened the discussion for various issues like belonging, home, identity, and several social issues. Then, there’s artist, poet and art educator, Kavitha Balakrishnan’s works, which primarily consist of written texts while Radha Gomathy, a Kochi-based artist has made an installation of 87 drawings created on her mobile phone. PS Jalaja’s works are a commentary on socio-political issues and Kajal Deth has depicted the lives of coir workers in her series of photographs. Siji Krishnan painted portraits of the people in her neighbourhood, during the lockdown while Chennai-based Parvathy Nayar has a series of black and white graphite drawings.

As Sebastian Verghese, a US-based artist exclaims, “Only Bose could pull off this almost impossible task. This show is historical and I am sure it will energise Kerala’s art scene. My participation is my way of showing solidarity.” Anoop Panicker also voices similar sentiments, “The very title of the show, a line from the poem by Vallathol Narayana Menon which means ‘The world is one family’, speaks of inclusiveness and that is what is the most important aspect of the show.” This monumental show, which is bound to go down in Indian art history, has helped all the artists forge new bonds, kept our spirits alive during the darkest of times and made us realise that the world is indeed one family.