- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

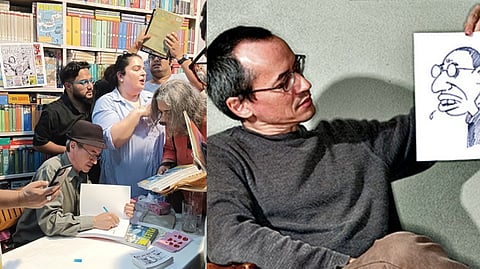

It was a rare Sunday afternoon in Delhi, marked by an unexpected bustle as over a hundred Delhiites queued eagerly outside two beloved bookstores: Midland in Aurobindo Market and The Bookshop Jor Bagh.

They had gathered in anticipation of meeting Joe Sacco, the celebrated Maltese-American graphic journalist known for his raw portrayals of conflict zones in works like Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza.

For Sacco’s admirers in India, this book signing offered a rare opportunity to connect with the man whose art has so powerfully captured some of the most haunting human stories of the past three decades. By 2 pm, a diverse crowd had assembled — academics, artists, writers, and enthusiasts of graphic novels — creating an atmosphere filled with curiosity and reverence.

A graphic impact

Outside the bookstore, a small, informal setup awaited his arrival. Encircled by chairs and set with a table, microphone stand, and a tray of sliced watermelon — a symbolic reminder of the ongoing crisis in Palestine — attendees sat in quiet expectation, waiting for Sacco to arrive. Said’s words came to mind: “The people he lives among...are history’s losers — banished to the fringes where they seem to be despondently loitering.... With the exception of one or two novelists and poets, no one has ever rendered this terrible state of affairs better.” Sacco’s work had evidently struck a chord here, resonating as a shared experience of struggle and resilience.

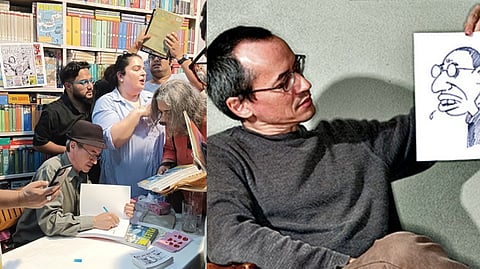

On his arrival, seeing the crowd, he acknowledged with humility, “I had no clue that so many people knew my work in India. I knew a few fellow comic artists and writers, but this has been a shock and a surprise.” The gathering was clearly a hopeful sign for the future.

Sacco’s impact on graphic journalism is profound. His works — grounded in reality and unflinching in their portrayal of suffering — have challenged the boundaries of both comics and journalism. His notable work Palestine, a collection of nine graphic novels documenting his two-month stay there in 1991-92, is emblematic of his unique visual storytelling style.

This work, along with others, has earned him numerous accolades, including the American Book Award (1996) and the Ridenhour Book Prize (2010). The Palestinian-American intellectual Edward Said, who wrote the foreword to Palestine, commended Sacco by saying, “Certainly his images are more graphic than anything you can either read or see on television.” Sacco himself articulated his motivation in Journalism (2012): “I chiefly concern myself with those who seldom get a hearing.”

Vignesh, Sacco’s friend, explained, “His visit to India is pretty random. He’s here to catch up with friends, and then a few events sort of conglomerated together. He’s also been running some workshops at Ashoka University.”

Learning from Sacco

In Kushinagar, he delves into the lives of India’s ‘untouchables’, people who, in his words, are “hanging onto the planet by their fingernails.” As the afternoon unfolded, the scene outside Midland witnessed people clutching copies of Palestine and The Fixer, among them Ita Mehrotra, artist and author of Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Story, filmmaker Sameena Mishra, and many more. Many attendees were there not only for signatures but to share how Sacco’s work had shaped their academic or creative pursuits. Some held theses and research papers, hoping to discuss their own studies with him, though time was short due to another scheduled event.

Ajith, a PhD scholar from the Centre for English Studies (2019), based his research on how Sacco’s mastery of the medium enables readers to see, look, and think differently. “My question was on the vision, inhabitation, and hapticity of the comic, and how this genre helps us navigate a post-truth world,” he shared. Similarly, Aparna Pathak’s MPhil on Sacco’s work from Jamia Millia Islamia in 2018 focused on Drawing Conflict.

Making hard choices

There is a lot one can learn about journalism and ethical questions of the profession through his work, as it retains a self-reflexivity. In Journalism, he explains, “By admitting I am present at the scene, I meant to signal to the reader that journalism is a process with seams and imperfections practised by a human being.”

His commitment to unfiltered storytelling has always taken precedence. In an interview with Chris Hedges, he said, “You’re often hearing things, and you realise this won’t sound so great for the greater cause, but then you have to decide if you’re an activist...or if you’re a journalist who’s trying to, as much as possible, tell the story honestly.”

Sacco has always leaned towards journalism, believing that even difficult truths must be told. He aims to depict people in conflict as real individuals with complex emotions, rather than as symbols of larger political issues. As he signed books at Midland, Sacco’s gaze often turned thoughtful, perhaps contemplating the lives he has brought to the page.

This article is written by Prachi Satrawal