- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

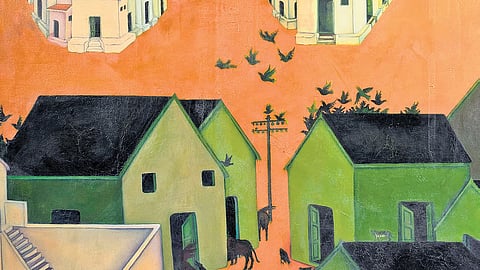

Veteran artist Gulammohammed Sheikh’s paintings are only one of the many inroads into his brilliant mind. An archivist, poet, pedagogue, singer and writer, he is a man of multiplicities and so his artworks too transcend easy forms and embrace everything from canvas to sculpture, accordion books to wood panels, and acrylic to gauche to casein. In his work, multiple dimensions coexist, like in a Christopher Nolan movie. Except he does not require you to necessarily slog over Reddit notes about wormholes and quantum physics—despite his incredible capacity to play with both our understanding of time and space. His work, in effect, creates, sustains and populates world within worlds, each artwork working like a colony of bees, active and alive.

All of these claims about Sheikh’s work can be verified by simply walking into the currently ongoing Gulammohammed Sheikh retrospective—‘Of Worlds Within Worlds’; on till June 30 — at Delhi’s Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

Encompassing over 190 artworks, created over a span of 60 years, the exhibition was previewed on February 5, followed by a soirée, attended by the eminent artist himself. Talking slowly but assuredly in his husky voice, Sheikh enthralled this hall with timeless stories from his life, often referring to how personal events collided with political shifts in the country, informing both his artistic sensibilities and civic duties.

The archivist

Curated by Roobina Karode, director, KNMA, the exhibition is not only a comprehensive journey through Sheikh’s oeuvre, but is also a refresher on modern Indian history in many ways. Even in his most intimate, personal artworks, Sheikh is referencing the world outside of his (artistic) world. Karode has been familiar with Sheikh’s work for nearly 50 years, since the late 1970s, when Sheikh was an art history teacher in Baroda, where Karode studied. This is around the period Sheikh made one of his most arresting political paintings: ‘Man I’, exhibited at the KNMA. A headless figure sits in the centre of a red road, flanked by mustard-yellow planes. Sheikh painted ‘Man I’ during the Gujarat riots of 1969-70.

Sheikh bears witness to history in his work, and refers to not just political events, but also forest fires and climate change. He says: “I do respond to contemporary events like the Emergency, the rise of communalism etc. ‘City for Sale’ refers to communal conflagration in cities like Baroda where I live, the ‘Kaavad Called Ayodhya’ deals with the demolition of the Babri mosque quoting imagery available online and from traditional paintings.

The intention is to make the viewer contemplate on the events to find ways of dealing with them.”

Karode adds in the note accompanying ‘Ahmedabad: The City Gandhi Left Behind’, the idea is to explore “forms of reconciliation in a world torn apart by sectarian conflict”.

The artist

A lot of Sheikh’s work carries what Karode calls “travelling motifs”—his early representations of horses, which he describes as the “horses tethered to the tongas that I knew of in my childhood unlike the ‘timeless’ horses of [M.F.] Husain,” to his lifelong fascination with the teachings and poetry of Kabir—who is present in many of his paintings as a figure himself. Many of his paintings are palimpsests—maps of cities become historical documents, personal photos of friends and family become the base for a narrative painting, mixing various mediums from paints to iron bars in the artwork.

Some of the most captivating pieces on display are his accordion books. Book of Journeys—which took over 10 years to complete—placed in the centre of one of the last rooms at the retrospective, demands keen attention. Each of its flaps seems to carry a phase of Sheikh’s life, and in its entirety, a sum of all of his other artworks. “The accordion format enables you to shuffle pages to make a series of permutations and combinations,” he says. “I carried Book of Journeys wherever I travelled and painted images of the places I visited; like for instance Civitella in the region of Umbria in Italy and Dalhousie in Himachal Pradesh …you may find Kabir laying out his chadariya before an

angelic figure, followed by images of a hill-side town in India … Painting is a kind of journey, and I try to capture what I encounter by making images flow into each other.”

The legacy

For Karode, and many generations of artists, Sheikh seems to have opened a door, to let in the magnanimity and multiplicity of the world outside. By opening this door, one may argue, the distinction between the inside and outside is revealed to be arbitrary. Talking about Sheikh’s legacy, Karode says: “I grew up understanding from him and his work that the world is not a singular place, it doesn’t carry a singular meaning … The idea of simultaneous viewing and happening … is what I wanted to represent in the retrospective.”

Karode further says, “There is a collision of time and space; history and present collide, myths and reality collide … this is all possible because he understood that there was no linear perspective method to [Indian] art as seen in the West during the Renaissance … Through Sheikh, we realise that we have richer ways of spacemaking and storytelling.”

Sheikh himself regrets the standards of art practice and institutional support for artists in India, as he has repeatedly addressed in many of his other thought-provoking interviews as well. On M.F. Husain’s artwork being removed from the National Gallery in Delhi, Sheikh says: “It is unfortunate that art has become an object of assault in recent times. Much of it arises on account of ignorance of art practice.”

He continues to paint and teach and turned 88, on February 16. One of his most recent works at KNMA is ‘Kaarawaan’, completed in 2023.

Occupying a long wall by itself, the canvas, over six-and-a-half feet in length and 21 feet in width, is breathtaking in scope, no doubt, but an equally profound statement of Sheikh’s legacy. The mythic, poetic, and historical combine in this painting, in which an ark surrounded by turbulent waves carries Mughal,

Renaissance and modern artists as well as many of Sheikh’s personal spirit guides, along with his favourite motifs recurring — trees on the stern and an angel with burning wings flying overhead. The curator’s note \describes it as a “whole world encapsulated in an ark that sways with the turbulent sea … the artist has gathered what he holds dear and set it away in search of safer shores.”

(Written by Kartik Chauhan)