- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

Folk traditions in music are observed punctiliously. One of these are Chindus or Tamil couplets or poems set to a particular meter. Devotees of Lord Murugan sing Kavadi Chindus as they carry the kavadi on their shoulders to the sacred shrine in Palani in Tamil Nadu. India’s most illustrious musical activist TM Krishna is adept at singing them.

He innovated on the lyrics by setting to tune a Kavadi chindu on Babasaheb Ambedkar—something he loves performing at most of his concerts—written by the famously controversial Tamil rebel writer Perumal Murugan. Murugan was targeted by groups for portraying a childless woman who participated in a sex ritual during a temple festival in order to have a child in his 2010 novel Madhorubagan. The writer sees his collaboration with Krishna, who recently performed in the twin city of Secunderabad and Hyderabad at Kalasagaram’s 55th Annual Cultural Festival of Music, as a “small instrument to make Carnatic music relevant to the modern time”.

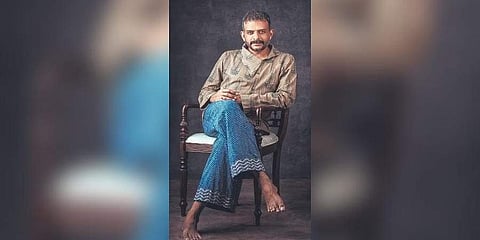

In a nutshell, the melody of defiance towards oppression and creative freedom symbolises the music of TM Krishna. The charismatic singer is a harmoniser of contradictions on stage, deviating from the conventional Carnatic kutcheri paddhati. Conventional grammar, social or musical, is anathema; he is known to start a composition with a krithi and perform a varnam in the middle of the concert. To someone uninitiated in Carnatic music, a TMK performance is a lesson-of-sorts with your favourite teacher. Through light-hearted banter and brief explanations, he whets your interest in the genre.

The singer, writer, activist and Magsaysay award-winner believes in connecting to his audience, shattering all notions of space an artiste must inhibit: a dominant force in full control of the raga. He takes his time, delicately teasing each lakshana one by one, before uncovering the entire bouquet of notes. Handholding each audience member, he slowly elevates the listener through each note, often stopping midway to explain the relevance and meaning, and reconnecting seamlessly from where he had broken off.

Murugan is not his first social justice muse. About six years ago, he started his now-famed collaboration with the Jogappas, a transgender community from Karnataka, who sing paeans and bhajans in praise of Goddess Yellamma. Krishna insists on not terming the collaboration as fusion. “The Jogappas helped me go beyond my own limitations,” the singer maintains. As the Jogappas sing in their distinct folk style accompanied by their string and drum instruments such as chowdiki, suttaga and tala, Krishna effortlessly joins with his Carnatic raga creating a rare mélange of sounds and notes.

Krishna has also nurtured the little-known Nadaswaram and Thavil artistes through his Sumanasa Foundation. Though these two important instruments are played at every auspicious occasion in South India, Krishna rues the fact that the artistes are yet to get mainstream attention. To address the issue of many fringe artistes lacking mainstream representation, he launched his own music festival, Urur Olcott Kuppam Vizha, in 2016. Renamed the Chennai Kalai Theru Vizha, it features diverse art forms at

a fishing village in Chennai. “It will take a few generations for Carnatic music to become socially representative,” says the Chennai-based artiste.

Krishna says the texture of his music has changed. “The sound that I seek when I sing now is not what it was a couple of decades ago,” says the 46-year-old, who launched a series titled NLBT (Not Limited By Time) on his YouTube channel in October 2021. The series invites various artistes across the music field to perform one piece. The only rider is that it must be at least 15 minutes long. To expand the reach of Carnatic music—which he believes is largely exclusive—had prompted Krishna to start TMK Unplugged, during the pandemic to aid struggling artistes.

The ongoing project—conducted so far in Chennai, Bengaluru, Pune and Thrissur—is unique: the artiste performs in someone’s home with small groups in attendance. Structured as an intimate concert, guests donate what they deem fit and the entire collection goes to struggling artistes. “I prefer not to plan for the future, but remain very observant when some idea appears on the horizon,” he says.

TMK’s next big thing is titled the Edict Project. Through it, he plans to musically set Emperor Ashoka’s words to music and spark conversations on governance, the relationship between raja and praja, and the concept of dhamma. Krishna’s music is never over until he says ouvre.