- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

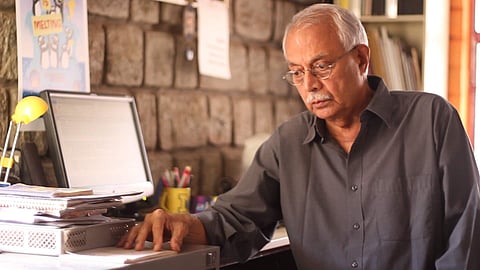

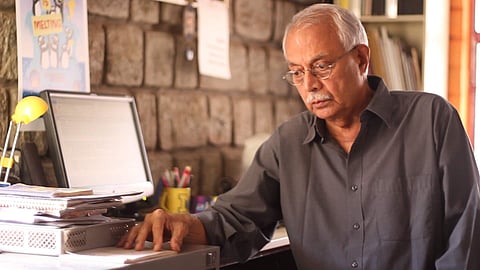

Penning over 50 original plays, adapting and translating scripts, Vijay Padaki the founder-trustee of Bangalore Little Theatre has worn several capes for his achievements in theatre. Being a management professional for over forty five years, he has also been active in theatre for the last sixty years. Besides, he is also known for his role of institutionalising several activities of BLT, including the annual summer workshop for newcomers to the theatre, which has birthed several theatre personalities in Bengaluru. An actor, director, trainer, writer and administrator, he was recently in the spotlight, when he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award from ASSITEJ International. We catch up with him to talk about the award and his craft .

What does this lifetime achievement award mean to you as an artiste?

The award ceremony was overwhelming. There were about 500 delegates from nearly 70 countries. It was very satisfying on another count. Our Children’s Theatre work is not so visible. People remember BLT for their public performances. It was good that our Children’s Theatre got the recognition it deserved — outside the country before within! That was more important for me than the award itself.

It is said that your play Robi’s Garden is an outstanding example of Children’s Theatre. How does the play reflect your own artistic style and vision?

Robi’s Garden was a full play taken up in 2011 to pay a tribute to Rabindranath Tagore in his 150th birth anniversary year. While the whole world was looking to perform his ‘classics,’ we decided to do something original, to work on the lesser-known side of Tagore — his comical side. We took his work for children and adapted it for the stage. It included verse, short stories, plays and sketches (his ‘riddle plays’), fantasies, autobiographical writing, (esp. his childhood memories) and the letters to his grand-daughter and other children. The play was one of my best offerings in BLT’s annual flagship Children’s Theatre programme. It had a large cast, with both children and grown-ups on stage, it was a family entertainer, it had a racy script, it had an imaginative stage and innovative props, it stimulated the children’s audience to imagine a world beyond the syrupy stories inflicted on them at school and home and most of all, it incorporated the best of storytelling traditions. It turned out so good because it was not a mere translation of the original works. It would be just a literary piece then. Taken up as an adaptation for the stage we could make the spirit of the originals come alive in the English language and pay a joyous tribute to Robi-da! The revered poet Sankha Ghosh was hugely pleased with the adaptation.

You trained earlier as a clinical psychologist. What made you take to the theatre?

I have taken a long and winding road over the last sixty years. Biology, clinical psychology, applied research in organisational behaviour, teaching and research in management and consulting in large social development programmes. The training as a clinician in the earlier stage of my life remained valuable in all my work — for grasping the essential conditions that govern both function and dysfunction in human organisations. It was also a most valuable perspective to bring into the theatre. Drama, all said and done, represents a never-ending struggle to come to terms with ourselves!

Can you tell us about the thespians who have had significant influence on your work?

The most influential were the remarkable couple Scott and Margaret Tod, who were also among the founders of Bangalore Little Theatre. They brought the experience of the Little Theatre movement in the UK to Bengaluru. Scott was an experienced director, Margaret an actress. Their most valuable contribution to BLT was the professionalism they injected into the group’s working. In later years, I had the good fortune of having (the late) Bansi Kaul as a friend. He was also an informal advisor when we were setting up the Academy of Theatre Arts. So was Feroz Abbas Khan. Their grounded experience in managing organisations in the Indian context was very useful indeed. I had a personal sounding board in Bhagirathi (Bagyam) Narayanan. She was also my best critic. The late evening chats with her were always educational.

Bangalore Little Theatre has been cultivating new generations of theatre artistes in the city. What was your inspiration behind starting it?

We realised very early in BLT that the health and robustness of the group had to be from investing in talent development and leadership development. It was a conscious decision to move away from the most common malaise in arts organizations — the founder-centric syndrome. Through the highly participative ethos in BLT we have had a continuing string of leaders in running the organisation. In addition, we have also had new directors all the time. That has come from structured training programmes for young directors. The last programme was in 2023. And, of course, there has been the annual Summer Project on Theatre (SPOT), out of which have come so many of the artistes in the Bengaluru theatre scene.

BLT is seen as an ‘English theatre.’ How have you related to the Kannada theatre in Bengaluru?

First, it is necessary to state that BLT is an English language theatre organisation, not an ‘English’ theatre group. It may be useful to remind ourselves that the very origin of BLT in 1960 was to break the stereotypes of ‘Cantonment theatre,’ and to build a truly universal identity for the theatre work that BLT would do. Many of the founders of BLT were also stalwarts in Kannada theatre. They went on to become famous in film too. Within two years after starting BLT performed an original English language adaptation of the Sanskrit classic Mrichchakatika. For many years now we have been performing plays originally developed within BLT — all rooted in the Indian social context. Kannada theatre, like most regional theatre in India, has had its ups and downs over the decades. These swings are reflective of the larger socio-political conditions at the time. BLT has remained a companion of Kannada theatre all the time.

You are putting efforts to introduce and sustain theatre curriculum in schools and train teachers. Are you facing any challenges in doing that, given the academic system in India is still very traditional?

It is an uphill task! We knew that right from the start, of course. There is a poor appreciation of the value of theatre activity as part of schooling, let alone theatre as a curriculum subject. We have come to accept that we cannot get angry at the ‘school system.’ It is in many ways helpless, because it is part of a larger societal rot in which 95 percent marks are more important than oxygen itself. In such a system the word ‘theatre’ connotes entertainment and not experiential learning — which is what it really is. Nevertheless, we have made progress, one inch at a time. We are now building a network of half a dozen schools in which we have long term involvement. Our major achievement has been in developing the original methodology for theatre-in-education, which refers to the application of theatre techniques to enhance classroom learning.

How can theatre artistes better align their work with broader societal goals and values?

You can have a ‘theatre of indulgence’ and a ‘theatre of social responsibility.’ Many belong to the former category and are satisfied with audience ovation and green room parties. It can also be called F&F Theatre. A good part of the audience is family and friends. Even the choice of plays may be determined by the kicks to be had from the performance. The origins of the theatre in the anthropological sense are in storytelling traditions that questioned beliefs and assumptions. This meant a deep social connection. I have always maintained in our training programmes that artistes must get out of their comfort zones and get to know the realities around them. They must absorb more, opine less. They must get themselves dirty. You cannot be true to your art from your laptop alone.

How do you see the future of theatre evolving globally, especially with the rise of digital media?

The trends in content are very exciting. Theatre artistes world-wide are questioning the world and its past assumptions more and more. New writing is more demanding on the audience, more dissonance producing. We are not there yet in India. The political environment in the recent past has turned hostile to artistes who question things. They are seen as troublemakers. Technology and digital options can come only after we have our content right. It can never be technology for technology’s sake. The really big question — with no clear answer yet — is what AI can do to make the content socially purposeful.

Email: sonia.s@newindianexpress.com

X: @Soniasali98