- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

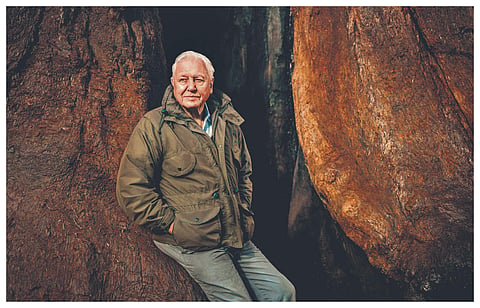

The last time we were this excited about plants was 26 years ago in the series Private Life of Plants, where they utilised the time-lapse feature, giving plants a new lease of life by speeding up the action so that you could literally watch them grow, blossom, and so on. This time, with The Green Planet we are promised an animated, aggressive and eccentric plant kingdom that has been re-imagined and accessed like never before. Naturalist Sir David Attenborough’s presentation lends it a deliberately wild narrative bend where there are parasitic plants that smell out their host, cacti that are dangerous while some plants are strangling their prey. The celebrated English broadcaster talks about why we need a show on plants and how this series is different from any other:

Why did you decide to focus on plants for this series?

Private Life of Plants, exploited time-lapse, bringing plants to life by speeding up the action so that you could see them grow, blossoms open, and so on. But what could we do that was new? Well, the thing that really is new, is that in Private Life of Plants we were stuck with all this very heavy, primitive equipment, but now we can take the cameras anywhere we like. So you now have the ability to go into a real forest, you can see a plant growing with its neighbours, fighting its neighbours or moving with its neighbours, or dying. And it's that in my view, is what brings the thing to life and which should make people say, ‘Good lord, these extraordinary organisms are just like us’. In the sense that they live and die, that they fight, they have to fight for neighbours, they have to learn to reproduce and all those sorts of things. But just that they do them so slowly, so we've never seen that before. And that has a hypnotic appeal, in my view.

Plants fight one another, plants strangle one another. And you can actually see that happening (in real time). You can suddenly see a plant putting out a tentacle! Now you know it can't actually see, but you can see it trying to find its victim. And when it does finally touch the victim, it wraps around it quickly and strangles it. You know, it's pretty tough stuff.

How was it travelling the world for this series?

In a sense, the series itself is slow growing, like plants. We started [filming] a long time ago, before COVID. And so I was dashing around interesting places, in California and so on, in a way that hasn't been possible for the last two years. So I appear in all these different parts of the world quite frequently, more than any other (series) for some time.

Did this feel like an important time to be making a new series about plants?

Yes, the world has suddenly become plant conscious. There has been a revolution worldwide in attitudes towards the natural world in my lifetime. An awakening and an awareness of how important the natural world is to us all. An awareness that we would starve without plants, we wouldn't be able to breathe without plants. The world is green, it's an apt name [for the series], the world is green. And yet people's understanding about plants, except in a very kind of narrow way, has not kept up with that. I think this will bring it home.

The world depends on plants. It's a cliche now, every breath of air we take, and every mouthful of food we eat, depends upon plants. I also think that being shut up and confined to one's garden, if one is lucky enough to have a garden, and if not, to having plants sitting on a shelf, has changed people's perspective. And an awareness (has grown) of another world that exists to which we hardly ever pay attention to in its own right. Of course, we do gardening programmes and have done since the beginning of television. But this is not about gardening, this is about a parallel world, which exists alongside us, and which is the basis for our own lives, and for which we have paid scant attention over the years.

Anybody who takes a walk probably sees more plants than you see animals, so why do you think people have not been as engaged with plants as they been with animals?

Because they apparently just sit there being a plant. You could either take them or leave them or you could dig them up or throw them aside. They don't react, they don't resent it, they just die. We don't engage with plants enough.

And David, in your travels on the series, you interacted with lots of plants. Are there any plants that really stuck in your mind?

One of the really great, profoundly moving experiences, was to go to the Giant Sequoias in California, these enormous trees. It's not an accident that there’s a cathedral like feeling when you go amongst them. They are immense things, some of the tallest ones are enormous. But what this programme did was to use another of the inventions that you might think had very little to do with plants, technical inventions, that changed natural history photography in the past 10-20 years - drones. When you see the final sequence in the programmes and (the camera) suddenly rises above the tree tops and you see these giants - it's a marvellous sequence.

And you have a very scary encounter with a cactus didn’t you?

Yes, I mean, the Cholla really is a physical danger. It has been very dense spines in rosettes, so they point in all directions. And if you just brush against it, the spines are like spicules of glass, I mean they are that sharp and they go into you and you really have trouble getting them out! So that is a really dangerous plant. The Cholla is an active aggressor. I mean you feel you better stand back and you better watch out (for it).

So we are used to seeing images of animals fighting for their existence, but in this series we also see that plants are doing the exact same things?

Plants fight one another. There are many examples but let me just take one that's in our own hedgerow. There's a plant called the dodder, which because it's parasitic, lives by inserting a feeding system into other plants. But because it can't see, it does this by using receptors to sniff out its prey, and suddenly it wraps round this stem and starts a process of piercing to steal nutrients. And that's an aggression, which happens in the hedgerow. And I bet the number of people who are actually aware of it is not very high.”

In the water episode there's a big scene in the Pantanal (Brazil), how did you use time-lapse for this scene?

Well, water lilies are extremely aggressive. And their battleground is the surface of the lake and the surface of the water, so it's a very narrow battle. The Giant Water Lily which produces leaves famously which can hold a small baby, has a bud that comes up loaded with prickles. And it comes up into the surface and starts expanding, with these spikes pushing everything else out of the way. And in the end the lake ends up as solid Giant Water Lilies butting up against one another, with no room for anything else at all. It's one of the most empire building aggressive plants there is. Everybody says how wonderful it is, but nobody says how murderous it is.

What would you hope that the audience will take away from watching the series

That there is a parallel world on which we depend, and which up to now we have largely ignored if I speak on behalf of urbanised man. Over half the population of the world according to the United Nations are urbanised, live in cities, only see cultivated plants and never see a wild community of plants. But that wild community is there, outside urban circumstances normally, and we depend upon it. And we better jolly well care for it.

On Sony BBC Earth,

from April 11 onwards, at 9 PM.