What taking off Mani Kaul’s glasses mean for Mita Vasisht’s first film as director

By design, Lapdiang Artimai Syiem is, at times, watchful and tentative, receiving and responsive in her first lead role in a Hindi film, Mani Kaul and That Thing called the Actor. Just like Mita Vasisht was, when presenting Siddheshwari Devi, the great thumri singer of Benaras in the 1991 film by Mani Kaul, one of Indian cinema’s greatest auteurs and form-breakers. Common to both films is Vasisht. In Kaul’s film, she was the lead actor; in this one, she is behind the camera. Mani Kaul….is her directorial debut, and it is based on the actor’s craft, drawing from Vasisht’s experiences of training herself not to ‘become’ another Siddheswari but present her spirit in line with Kaul’s vision of how Siddheshwari herself came to be.

In that journey if Vasisht drew from life, from the history of gestures of great actors like Helene Wiegel, German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s partner and collaborator in the Berliner Ensemble, she also drew from her own training in the Natyashastra taught to her at the National School of Drama; Syiem, also an NSD-trained actor collaborated, says Vasisht, in much the same vein.

Vasisht’s film, shown recently at the India International Centre, while being of the Mani Kaul school is not about Mani Kaul but a synaesthetic experience of the actor’s world. And Syiem presents her director’s life and processes when Vasisht was an actor for Siddheswari, down to the loosening of limb, the act of watching, listening, thinking, halting, the touching of a swing, the opening of her mouth to sing on a ghat of Benaras as actorly exercises. In her film, what happens before the film starts, the nuts and bolts of the actor’s craft, is key.

Vasisht’s essay film was 12 years in the making. It is a singular achievement in film – unless one thinks of Satyajit Ray’s Nayak, a narrative film on a matinee idol’s exhaustion with fame -- of the actor’s work on her craft, her inner life, her internalisations – the heavy lifting the audience does not see – and her contribution towards the making of a film conventionally considered the director’s medium.

Vasisht appears only once in the film, towards the end, when, in a voiceover, she says the character and the actor are separate and must stay separate, perhaps echoing what Aristotle, and Kaul too, believed in – that the work of the actor is just to present a character without psychology, without motivations, without trying to fix identities and meanings onto them. The film begins with Mani Kaul’s glasses. Mita Vasisht knows how to wear them but she has shown her own hand.

Excerpts from a conversation:

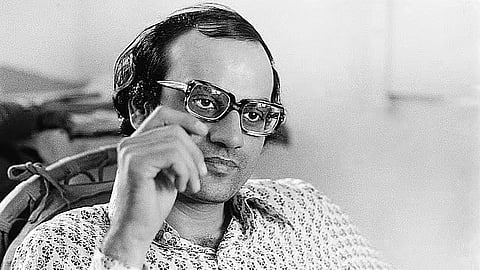

One feels tempted to call this film Mani Kaul’s Glasses. You’ve taken the literal story of how, as a child, he came to wear glasses, and how he began to look at things differently than when he was without those glasses, and transformed that story into a metaphor -- his particular way, as an artist, of looking at things, people, actors differently.

A lot of the film is based on 33 years ago, of actual notes including of the three months when I worked with Mani on Siddheshwari. It was much later that I got to know about him being a young boy who saw the world with a blurred vision for 10 years of his life, and I imagine what it must have been for him to suddenly find the ability to see very clearly. And yes, you're right I extended it to a metaphor of what it means to be this particular person who never took seeing for granted. Mani had an extraordinary way of looking into the very soul, the heart of things.

So, that's why there’s that recurrent line in my film, which is, when we see, what do we really see, do we see form or the inherent nature of the thing or that which is hidden. And, as an actress, I think it is the finesse of acting to enter a state of being where what you’re showing is giving a sense of what you’re not showing. And that is what great acting I think is and I learned that by working with Mani (Siddheshwari, Ahmaq, 1991), and also, before that, with Kumar Shahani (Var Var Vari, 1986).

Mani and I were collaborators. It was not a guru-shishya relationship because as a young actress, after four years of training, I came to the table, as they say, with every part of the actor's craft that had been taught to us at the National School of Drama. We were the generation of actors that came prepared and did not expect that a director would tell us what to do. I mopped up Mani like a sponge, in terms of his ideas. I do say in the film that I would lean on to every single word that Mani spoke. So, whatever he would tell a cinematographer, I would try and interpret it as an actor.

What is the quality you were looking for in your lead actor? Syiem’s north-eastern identity is unmistakable. So when she practises being Siddheshwari before miniature paintings, what kind of encounter were you setting up?

Lapdiang Artimai Syiem, from Meghalaya, is a trained actress from the 2012 batch of the National School of Drama. I chose her because I found she was the only person who, after NSD, had continued with a very intense engagement with the theatre, with experimenting with new work with the body. She was doing workshops and collaborative work, not just in her own tradition, but also internationally while being rooted in her own tradition. I saw in her what I was as a young person, seeking roots but at the same time open to the vastness of many other traditions.

Initially I had contacted her in 2015 but the whole schedule went for a toss in 2017, a day before we were to start the shoot. She just said, ‘It’s okay, don’t worry, whenever you're ready, please let me know.’ So, there was a kind of, you know, elegance she has as a person. The thing that I saw in her was that she wasn't asking questions like, what if I get another project which is better? All the actresses that I interviewed in Mumbai, I could read their minds almost as soon as I met them that they were weighing the scales and thinking, will this help give me a fillip in my career or not? Lapdiang was a pure, pure artist, and that's the person I wanted for my film.

There is an interesting scene where life interrupts the actor’s music lessons with her teacher (played by Armaan Dehlvi). Were you also trying to show an aspect of Kaul’s style and belief that an actor is not a given – but produced through the journey of filmmaking, which is perhaps why Mani Kaul wanted you to learn painting, dance and music before the shooting of Siddheshwari began – something that you showed in the film?

The singing session being interrupted is again my fictionalising. I wanted to put across the idea that real life, if we look into it deeply, has a lot to offer.

As a young actress, who had just begun living in Bombay, I used to sometimes lean over my sixth floor balcony on days when I had no shoot and watch a slum below where many things would happen. And one of them was this fight between two women at a water tap. And it was a fantastic fight because they were, in a way, moving in circles, and it actually looked to me like a dance.... A lot of real things are woven in a fictional manner to allow the aesthetic principle to create the film.

What was the difference between working with other directors and Mani Kaul or Kumar Shahani?

The beauty about Mani and Kumar was that, for me especially, even their scripts were like metaphors that you had to decipher. You had to dive deep into yourself, into everything, your body, your mind, your skin, your literature.

And it makes a lot of difference if you have studied. And I had already done my MA in English before joining formal training in theatre. And all this helps you to be able to be really excited about the fact that Mani's and Kumar's scripts were not the usual scripts that demand ‘character building’, and storytelling. I think of their cinema as epic cinema quite like Ritwik Ghatak’s. There's a dialogue in my film where I say that acting in commercial films and Mani's films, maybe I would even add Kumar's films, is not very different from acting in commercial films. Because in commercial films, you have to make larger than life gestures. Whereas in Mani and Kumar’s films, you have to find the gesture from the largeness of life. You are already in a state of elevated consciousness when you're working with their scripts. To start with, you have to be there, reaching out for something much, much beyond the everyday, the ordinary.

But I've always strived, even for other directors that I've worked with, to give them and the film or the role that I'm doing more than what is asked for, more than what is on paper. And I think that I've succeeded with that in just about every work I've done for any director, you know, other than Kumar and Mani.

It took you 12 years to make the film. How challenging was it?

A lot of people that I approached, for example, to do the cinematography or for post-production, the sound or this or that, were very wary of even touching the film because they felt, oh, it’s about Mani Kaul. And this is the actress. And, you know, she’s probably doing a self-indulgent, sentimental story about working in a film. So, my challenge was to actually find people who would give me the shots that I had planned, the way I planned them, and they had to be people who knew nothing about Mani or cinema.

And I was really lucky to find Omar Adam Khan for cinematography, there are three people whose names come in cinematography, but the principal photography is Omar’s. Did I ever feel disheartened? I just realised that making the film that you want to make on your own terms and the way you want to make it will always possibly be a challenge. And there is a great joy in accepting that.

A.M Padmanabhan, with whom I collaborated on the sound design, was somebody I had known, and he had been on the film from its inception. He was very sceptical about getting back to the studios. There were times when he’d be in hospital for three weeks, so, the work would get suspended and I’d say, okay, that's also part of the process. Madhu Apsara has done the final sound mix. He is probably the very few remaining great sound design/mix people from the world of 35-mm cinema, and I am enormously indebted to him for the final sound mix. He was also extremely close to Mani, as was Padmanabham; interestingly, whoever has come onto the film is from the world of cinema, and some of them have also known Mani and worked with him, so that was quite wonderful too.

Did Kaul or Shahani know you planned to make such a film? What are you thinking of making next?

The idea of making a film came after Mani passed away in 2011, and I also had notes from 33 years ago. I had also always wanted to make a film on our tradition of performance, which is actually far more all-encompassing than any other western acting theories in the world. I may work on a film on Kumar next.