- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

India is a treasure trove of ancient knowledge and architectural marvels, with historical sundials standing as enduring symbols of its astronomical heritage. These remarkable instruments, created centuries ago, showcase the advanced understanding of celestial movements and timekeeping in Indian civilisation. Built with precision and ingenuity, they often formed an integral part of temples, observatories and royal complexes, blending science with art.

One of the most renowned examples is the Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, a UNESCO World Heritage Site constructed in the early 18th century by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II. This astronomical observatory houses the iconic Samrat Yantra, the largest stone sundial in the world. Towering at an impressive 27 meters, the structure was designed to measure time down to an accuracy of two seconds. Its massive triangular gnomon casts shadows across meticulously marked scales, demonstrating the precision of ancient Indian astronomers. The complex, dotted with other instruments, reflects the era’s thirst for understanding celestial mechanics.

In Delhi, another Jantar Mantar shares the legacy of its Jaipur counterpart. This observatory, though smaller, features the ingenious Misra Yantra, a sundial that not only measures time but also determines solstices and equinoxes. Such instruments highlight the multifaceted role sundials played in ancient India—not just as tools for daily life but also as devices for astronomical research.

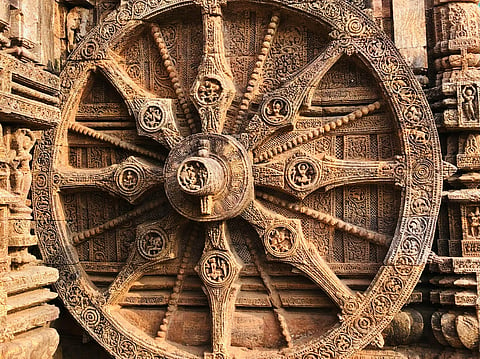

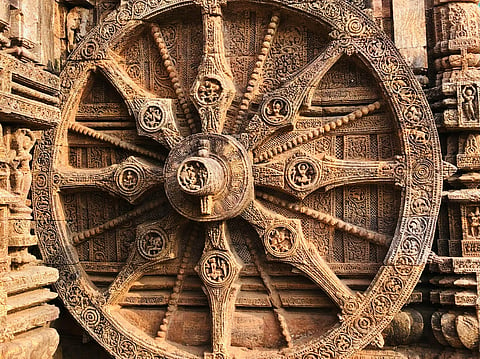

Further east, the Sun Temple in Konark, Odisha, reveals an extraordinary fusion of art and science. Built in the 13th century and dedicated to the Sun God, the temple’s intricate carvings include wheels that function as sundials. With their carefully designed spokes and placement, these wheels allow observers to calculate time by the movement of shadows. The integration of such functionality into a temple reflects the deep spiritual and scientific interconnections of the period.

In central India, the Vedh Shala in Ujjain stands as another testament to India’s astronomical prowess. Constructed during the same era as the Jantar Mantars, it was vital in mapping celestial movements. Ujjain, historically considered the prime meridian of India, was a hub of astronomical study and its sundials played a key role in calibrating time and understanding planetary motions.

These historical sundials are more than relics; they are symbols of a civilisation deeply attuned to the cosmos. Exploring these structures offers insight into a time when science, art and spirituality seamlessly coexisted, shaping India’s legacy.