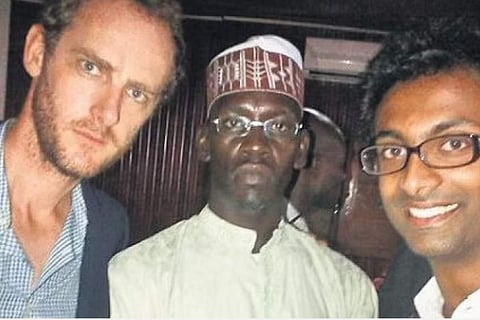

IIT-Madras and Yale-trained mathematician Anjan Sundaram is a chronicler of war in African nations. His reportage is driven by the most basic of journalistic instincts – why would the world’s deadliest conflicts go unreported in large sections of the media? Born in 1983 in Ranchi, Sundaram’s debut book, Stringer: A Reporter’s Journey in the Congo (2013), is an account of a reporter whose endeavour is to capture the punishing reality of a lawless country.

His second book, Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship (2016), documents the persecution of journalists in Rwanda. Breakup: A Marriage in Wartime, his latest, brings to the fore genocidal killings in Central African Republic and the personal cost he paid to be a witness and to uncover the truth. Is there any connection between mathematics and war reporting? Perhaps.

Excerpts of his conversation with TMS:

How did Breakup: A Marriage In Wartime happen? Did the idea come from your years of reporting from Africa?

I wrote Breakup in the aftermath of my divorce, the birth of my daughter, and my reporting in the Central African Republic. The three were inextricably linked: my becoming a father, seeking out the Central African war after I heard rumours of genocidal killings about to begin there, and leaving home in rural Canada, where I was living at the time with my new family. Unlike my two other books, Breakup took nearly nine years to publish. It took me time to get over my marriage and write about its beauty. I thought I would spend the rest of my life with my now ex-wife, Nat. I had chosen to have a child with her. I wanted to write about the beauty of what we had shared without showing any resentment about what I had lost. This took time, discipline, and a great deal of reflection.

The situation in the Central African Republic forms the backdrop of your book. Your life at Shippagan in Canada is a contrast through. How did you manage to navigate the transformation?

Home is a vital place in the mind of a war reporter. In the Central African Republic, my journeys were typically structured like this: I would hear about a massacre, but vaguely. It would be hard to know who had killed whom, why, where exactly, and for what reason. I would only know that people -- sometimes a lot of people -- had been killed. And so I would set out to get as close as I could to that place, so I could learn more about it and report on it. I made this journey with great humility: I had to be willing to turn back at any time or wait a couple of days before moving forward. In each village -- at every tea stall or restaurant -- I asked locals if it was safe to move ahead. If they expressed any doubt, I had to wait. It is part of my job to be extremely careful in this way. And psychologically, home in Shippagan needed to exist as a place I could return to happily. I needed to know -- even if I didn’t do it -- that I could return home and be content there. This is why I juxtapose family and the war in this story of war correspondence. Both are important.

What is it like to be a witness to a war crime and subsequent humanitarian crisis? How does it affect a witness? Psychologically, emotionally?

I write my books in the first person for three reasons: I like to show the subjectivity of my narratives rather than pretend to provide an objective truth, I like to write from a position of ignorance rather than authority, and I need to process the emotions I’ve absorbed in the field. Journalism often aspires to an objective truth. By writing in the first person, I present who I am: a man who grew up in India and was educated in the US, to indicate to the reader that I am drawn to certain stories but that I also have certain blind spots. I invite the reader to travel with me through the war and my family story, in this subjective exploration. The reader chooses if they wish to join me.

Similarly, journalistic accounts are often presented as authoritative accounts of a place. I like to begin my stories often at the point when I know nothing -- or very little -- about a place. In this way, I establish a complicity with the general reader, who also might know very little about the place I am about to travel to. I tell the reader why I’m interested, and if they share in my curiosity, I invite them to sit on my shoulder and travel with me as we learn together. Finally, writing about myself allows me to see myself as a character, with a certain distance, and this helps me process the psychological weight of the events I report on.

How does trust deficit between communities play a pivotal role in war or conflict?

It is striking how when the Christian majority in the Central African Republic decided to go after the Muslim minority, little propaganda was needed. The majority of the population instinctively knew that the Muslims should be attacked, that they had forgotten their place as the minority in the country by daring to seize power, and that they should be put back in their place. What ensued was officially ethnic cleansing -- though I recorded genocidal intent among some of the leaders of the rebels doing the killing. The vast majority of the Muslim population was killed or driven out of the country -- and attacked as they and their unarmed children tried to flee. This deep distrust had been largely hidden for nearly a century. The Muslims’ desire to take power in the Central African Republic stemmed from a sense of humiliation from their defeat by French colonial armies in the late 19th century, when France took over Central Africa. Most of the world has forgotten this Muslim history, but local Muslim communities have harboured a desire to once again rule and recover their lost glory.

What are your future plans and your next book?

The breakup was an effort to complete and get out. Even to speak about it publicly weighs on me -- so personal is this story. It completes a trilogy, with my other books Stringer and Bad News, of my reporting in Central Africa. I am now working on accounts of my time in Cambodia and East Asia, while reporting on environmental defenders in Latin America. I’m also working on my first novel, drawing on my mathematical education.

‘It took me time to get over my marriage and write about its beauty’, says award-winning Indian journalist Anjan Sundaram. His new book Breakup reveals the personal price war correspondents pay to bear witness to humanitarian crimes across the world.