- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

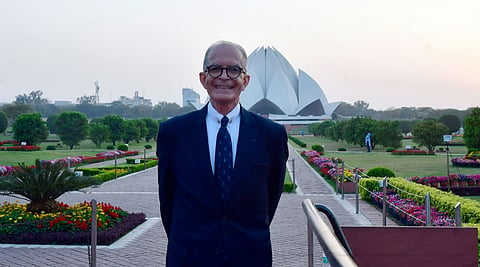

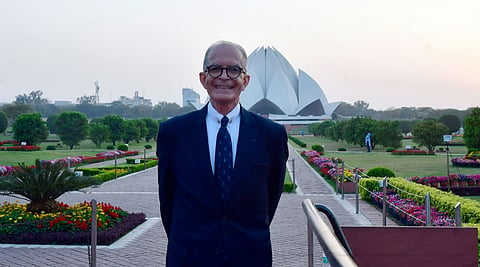

Even before the sun is about to set on the lawns of the Baha’i House of Worship (the Lotus Temple) and the programme to commemorate the 100 years of the community’s elected body in India begins, Kazem Samandari is everywhere. Samandari, the founder chairman of the French bakery house L’Opéra, is a senior member of the Baha’i community— numbering around 4,000 in Delhi and over two million in India—in the city. From greeting different religious leaders to diplomats and politicians, and connecting them to each other, he is working ‘the room’. But was there a time when he was perhaps the odd man out at social gatherings?

“Our family moved to Delhi in 2008. It happens often that I or my family are the only Baha’i in a room, at a conference, at an event or a social gathering,” he says. “But our faith teaches us to be open to other faiths so there is hardly any feeling of otherness. ‘In the room’ we find people who follow the teachings of Baha’u’llah so in that sense we feel as they are Baha’i too,” he says. This active embrace of others has ensured that no outsider stays so for long and this has made India receive Baha’i ideas and its people, taking from them what they will. In many quarters, Baha’is are seen interchangeably as people of a ‘faith’ or a ‘community’ with a certain worldview.

Who are the Baha’is?

Baha’u’llah, an Iranian aristocrat, was the founder of the Baha’i faith; he broke away from Islam in the 19th century. The main reason for the persecution of Baha’is in Iran, the land where their faith originated, is the fact that they admit no clergy and the Muslim clerics could not accept that a divine revelation, which Baha’u’llah claimed he had, could take place after Islam.

Among the social teachings that are salient to the Baha’i faith are the abolition of the holy war or jihad, in the sense of a war against other creeds (including Islamic ones) and faiths that is upheld by a few extremist groups; the obligation of personal and individual search for the truth; collective management of the affairs of the community without any mediation of priests; new marriage laws and (compulsory) monogamy’ new personal ordinances for fasting and prayers. These are some of the principles that are unique to the Baha’i faith and absent in Islam. But try explaining all that to the average Delhiite.

Who are the Baha’is?

Baha’u’llah, an Iranian aristocrat, was the founder of the Baha’i faith; he broke away from Islam in the 19th century. The main reason for the persecution of Baha’is in Iran, the land where their faith originated, is the fact that they admit no clergy and the Muslim clerics could not accept that a divine revelation, which Baha’u’llah claimed he had, could take place after Islam.

Among the social teachings that are salient to the Baha’i faith are the abolition of the holy war or jihad, in the sense of a war against other creeds (including Islamic ones) and faiths that is upheld by a few extremist groups; the obligation of personal and individual search for the truth; collective management of the affairs of the community without any mediation of priests; new marriage laws and (compulsory) monogamy’ new personal ordinances for fasting and prayers. These are some of the principles that are unique to the Baha’i faith and absent in Islam. But try explaining all that to the average Delhiite.

But there was no getting around his name—Adib was named after Baha’i scholar Adib Taherzadeh by his parents. Almost everyone has a question about that. ‘Kiske bhai hai tu? (Whose brother are you)’ I keep getting asked why my name is Adib if I’m not a Muslim. So, I just start with the Lotus Temple…,” he says. “One of my close friends’ parents hate me …this made me understand what my Muslim friends go through.”

A practice of study and reflection, and a continuous assimilation of aspects of other faiths is what keeps the community open and accommodative; this also impacts all those who come in contact with it. Gulam Rasool Dehlavi, 31, a Sufi scholar at the event, says he has been a dialogue participant at the Baha’i House for the past seven years. “It helps me deepen my understanding of various faith traditions. Orthodox Muslims have a problem with it. They feel it is a challenge to their clergy’s authority,” he says.

Are the community’s low-key activities one of the reasons behind the confusions about the community? Angamba Irungbam, 22, who works at the information office at the Lotus Temple, says: “Baha’is are not in the spotlight as we see our practice as a form of service which is why what we do has a certain spotlight-lessness. People also ask about the lotus, I say lotus is a prominent flower of India, it has nothing to do with religion (for us).”

Fariborz Sahba, the Iranian-American architect who, in 1976, built the Lotus Temple, often called the 20th century’s Taj Mahal, perhaps says it best. In a 2021 video interaction with other fellow Baha’is to explain what the building stands for and the uniqueness of its design, he says beauty, which is very important for Baha’is, “is seen as the magnificent perfection of god”, and that he has built a temple “not for my god, but for anyone who believes in a god, or may not believe in a god..,even if a person believes in a force, we have built our building for that”.

Under one roof

Prayer keeps most Baha’is, young and old, centred and in touch with each other. It is also an important point of contact with other communities. At these monthly devotionals, people of different faiths are invited to read from their own scriptures what has been best and wisely said on a pre-decided topic. Prayer topics as wide ranging as ‘Living the life’ , ‘War and Battle’, ‘Fruits’, ‘Trees’ and ‘The Golden Rule’ have, for instance, been discussed with a Vivaldi violin concert break, chants from the Gita to the anti-war anthem, ‘Guantanamera’ at sessions conducted by the Samandaris.

“What happens after the prayers is a unique conversation,” adds Mishra, “where it follows that we are all talking and praying about the same thing. What Baha’is do is to actively promote this feeling.”

But why are they so few in number? Samandari says as they have no priests, it puts responsibility on everyone to carry it forward. “It is easy to preach but difficult to live a life. It is also forbidden to proselytise in Baha’i but Baha’is can teach through their own example and explain the religion to anyone interested. Ours is a soft approach....it’s not about numbers but about influence", he says.