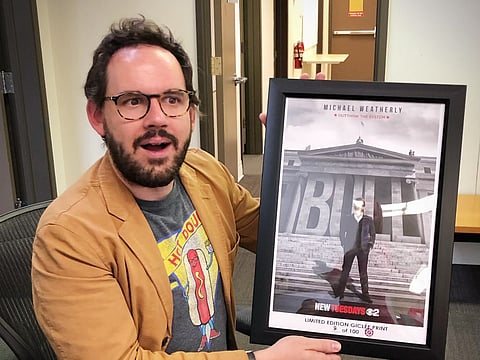

Exclusive: Writer Mike Costa, known for Lucifer, Transformers, Venom and G.I. Joe, shares a glimpse into his world, ahead of Hyderabad Comic Con

Mike Costa is a storyteller at heart, known for turning complex characters and beloved universes into human, emotionally resonant tales. From reimagining G.I. Joe to exploring the dark romance of Venom, Mike blends respect for canon with his own bold narrative vision, always driven by the thrill of sculpting the “right shape” of a story. He’s set to take the stage at the upcoming Comic Con event in Hyderabad and in an exclusive chat with Indulge, he shares all about his world of comics and the characters he treasures.

Mike Costa speaks about his comic world in light of the upcoming Comic Con Hyderabad event

What first drew you into the world of comics, and was there a specific story or creator that made you say, I want to do this?

The first story that made me truly love comic books, superhero comics in particular, was The Infinity Gauntlet. It’s funny how that story has become such a mainstream thing now, since it inspired the first 20 Marvel movies and everyone knows about the Infinity Stones. But when I first started reading comics, it wasn’t nearly as well-known.

My dad was a big comic book collector since he was a kid, and he had a huge collection, thousands of comics stored in long boxes in the basement. That’s what initially made me curious about comic books. When I was in 4th or 5th grade, I started buying comics myself with my own allowance money. It just happened to be right when The Infinity Gauntlet was starting. One of the first comic books I ever bought with my own money was Silver Surfer #48, which came right before the Surfer got to Earth to warn everyone about Thanos and the Infinity Gauntlet. It was the perfect time to start reading Marvel comics.

I thought Ron Lim, who drew Silver Surfer, was the greatest artist. He was the first comic book artist whose name I actually knew, and I used to draw the Silver Surfer all the time. At that point, I wanted to be a comic book artist myself. I didn’t even realize that writers and artists were different people. It wasn’t until I read more comics that I understood those were separate roles.

How do you shift gears between writing for established universes and developing your own original work?

That’s interesting, because as I mentioned earlier, my dad was a collector, so I’ve been reading superhero comic books literally my whole life. He mostly collected Marvel, but it didn’t take me long to get into DC Comics on my own. I’ve had decades of reading these characters, so I know them pretty well. Obviously, I can’t keep up with everything, and there are a lot of current series I don’t read, but I already know the characters themselves. I know Spider-Man, I know Batman—I feel like I have a really good sense of their personalities and how they’d act. It’s not that difficult for me to come up with ideas for them.

I often think about stories for Iron Man or Green Lantern just because I love the characters. As for original ideas, I don’t think there’s a huge difference. An idea is an idea. Just like you might have an idea for a horror story or a romance story—they’re different genres, but they’re still just ideas. It’s the same for me whether it’s an original concept or a story about Venom. What allows me to come up with ideas for established characters is the fact that I’ve spent so much of my life getting to know them. They’re part of my imaginative landscape.

Were there any particular books, films, or philosophical works that influenced your take on Lucifer?

This is a really interesting question, especially if your audience is familiar with or interested in the show Lucifer and wants to hear some behind-the-scenes stories. When we first started working on the show in season one, the initial idea was that every episode would be based on a Biblical verse. Our show-runner—which is the term for the head writer who’s in charge of the entire series—had prepared a list of verses before day one of the writer’s room. I was one of seven or eight writers, depending on the season, and every day, we’d meet in a big conference room to brainstorm ideas for upcoming episodes.

At first, we tried sticking to the show-runner’s concept of building each episode around a specific Biblical verse, but we realised you can’t structure a show that strictly around one text. It also became clear early on that the Lucifer we were writing about wasn’t the same Lucifer or Satan from the Christian Bible. Our version of Lucifer essentially says, “I didn’t write that book. That book was written about me. Would you think a book about you would be accurate?” That was our way of explaining that our story existed outside traditional Biblical canon.

We approached Lucifer as a character. The key idea was that he’s like a little boy who’s angry at his dad. He acts immature, he doesn’t want to grow up, and he refuses to take responsibility. His dad kicked him out of the house, gave him a terrible job he didn’t want, and made him the scapegoat for all the evil in the world—something he wasn’t actually responsible for. So Lucifer decides he’s done with all that and just wants to have fun. He’s constantly trying to outrun his problems through pleasure and distraction. Focusing on that emotional foundation made him much more relatable and interesting than trying to graft on complicated philosophical or theological layers.

That said, we did have a lot of discussions in the writer’s room about how hell works, what punishment for sin really means, and how guilt operates on a cosmic level. We talked about questions like: who decides what’s good or bad? In traditional Christian belief, that’s God, but our version of Lucifer didn’t fit neatly into that framework. So we created an alternate concept of sin and morality—something more universal and progressive.

Ultimately, we wanted to move from the idea of hell as a place of eternal punishment to one of redemption and healing. By the end of the series, hell isn’t there just to punish; it exists to reform and educate souls. Lucifer’s time on Earth, and especially his experience in therapy, taught him that people can change and heal. That became the emotional and philosophical core of the show: the belief that even the worst person has the potential to change, and they should always be given the chance to do so.

What story of yours feels the most personal, even if it's hidden under layers of science fiction or fantasy?

Another great question. All stories are personal in some way because they come from you, but I think some of my work on G.I. Joe, specifically the first few stories about an undercover agent called Chuckles, might be my most personal work. At the time, I had never served in the military, never killed anyone, and had no experience with terrorists, murderers, or arms dealers. I also hadn’t traveled internationally—I’d only been to Canada a few times and to Mexico a handful of times—but I was writing a story that took place all over the world about a guy who’s a killer and goes undercover. Fundamentally, that character’s life had nothing to do with mine, but I still wrote a lot of myself into him because I didn’t know any other way.

I think these stories feel personal because I was writing completely by the seat of my pants. I didn’t have a real plan, and I didn’t yet have the skills to approach writing as the craft I understand now, almost 20 years later. I recently went back and read some of those early comics, and certain scenes, lines of dialogue, or story moments immediately reminded me of what I was thinking and feeling when I wrote them. Everything I had experienced or heard about found its way onto the page because I was like a giant vacuum, absorbing the world and putting it into the story. I didn’t have the tools to craft a story with precision yet, so I just used everything I could, which made it an incredibly exciting time.

Venom stands out as one of your most character-driven series, what did you want to explore with Eddie Brock that hadn't been done before?

I consider Venom to be a love story. It’s about a toxic relationship between Eddie and the symbiote. Maybe “romantic” is too strong a word, but it is a relationship where two beings bring out the worst in each other, yet they can’t let go. There’s an addiction to that connection, even though it causes pain and makes both of them worse individually and together. That’s the dynamic I wanted to explore with Venom.

This aspect had been touched on in the initial stories by David Michelinie, who created the character with Todd McFarlane. Eddie would refer to the symbiote as “my sweet,” which added a vaguely romantic element that always stuck with me. When I started reading comics, Venom was still a relatively new character, and his popularity made a big impression on me. So when I got the chance to write him, that was the element I wanted to bring to the forefront.

I wanted to show that this isn’t just a guy in a suit that gives him powers—it’s a relationship. That’s why I had them essentially have a child. The symbiote gives birth again, and they bring a child into a world shaped by their toxic bond. It was a way to explore the consequences of that relationship and the complexity of their connection. That lens—the toxic relationship—is the one through which I always approached Venom.

The tone of Venom is psychologically rich, almost noir. What inspired that darker emotional angle?

My first issue of Venom opens with a quote from Heart of Darkness: “I should be loyal to the nightmare of my choice.” I thought it perfectly encapsulated the relationship between Eddie and the symbiote.

It’s not actually the first issue I wrote, but it’s the first issue where Eddie and the symbiote are Venom again, reintroducing that relationship. And I’ll admit, for the first time exclusively in this interview, that I didn’t pull that quote directly from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. I actually got it from the epigraph of a novel called The Big Nowhere by James Ellroy, a noir police detective novel set in 1950s Los Angeles. So I stole the quote from a book that stole it from another book—but the book I stole it from was a noir novel.

You have handled universes like Transformers, G.I. Joe with huge fan bases. How do you balance honoring legacy with introducing fresh ideas?

This is another fantastic question. To me, the balance in writing stories for Transformers, G.I. Joe, or any established universe comes from how much I love the canon of that universe. Particularly with some of my work on Transformers, I know that some fans didn’t love certain choices I made, and they felt I was betraying the legacy of these characters. I certainly saw a lot of online criticism accusing me of disrespecting the characters or ignoring elements of their history.

I don’t think those criticisms reflect writers hating the characters. If you are writing a comic with an established backstory, especially one that has lasted decades and is beloved, you almost certainly love those characters—you wouldn’t write them otherwise. The industry isn’t desperate enough to hire writers who hate the character. It’s easy to find someone who loves the character enough to write them well.

Even when I took over G.I. Joe and we were rebooting it, starting a brand-new history, the characters still existed as iconic figures. Those are the characters I wanted to write about. If I didn’t want to write those characters, I wouldn’t have.

Was there ever a creative risk you took with a licensed property you were initially unsure about, but ended up paying off?

Absolutely. There is a clear number one answer for this, and it’s a spoiler for anyone who hasn’t read my G.I. Joe: Cobra comic. In the third issue of my first G.I. Joe series, which is about an undercover agent named Chuckles who has infiltrated Cobra, his handler has been captured. He’s also had a romantic relationship with her—they’ve fallen in love during this intense time.

He’s brought into the interrogation room, and she’s sitting before him, essentially taunting him. She says, “I’m not going to tell you anything, so you might as well shoot me.” What she’s really telling him is: in order to save himself, he has to kill her so that Cobra doesn’t get her to talk and expose him. He realises that’s what she wants, and he does it. He murders the woman he loves.

This was an enormous risk. It was one of the first ideas I had for the story, and it was very risky because G.I. Joe was ultimately a toy brand. Even if it was a slightly edgy brand about soldiers, it wasn’t a world where the hero murders a romantic partner in cold blood.

I pitched it to Hasbro, and they said yes. I was honestly shocked. Writers often use a trick when working for a big company or ratings board. You pitch an excessively violent or outrageous scene knowing they’ll reject it, so everything else you want ends up looking reasonable by comparison. That was my thinking. But they let me do it. That moment was pivotal for my career. That risk is the one that paid off the most.

You’ve written across multiple genres, from superhero stories to mythic fantasy. What keeps you excited as a storyteller?

For me, what keeps me excited is always the challenge of figuring out what will happen next in a story. I’ve spent a long time trying to articulate this, and I’m still not sure I can do it perfectly, but I keep coming back to a metaphor I love: the Michelangelo quote about freeing the angel from the stone. You look at a block of marble, see the sculpture inside, and your job is just to release it.

That’s exactly how it feels to make a story. You know your characters are supposed to do certain things, but until everything fits together—the dialogue, the pacing, the structure—you don’t feel it’s fully realised. And when it does click, there’s this instant satisfaction. That process excites me more than anything.

Is there a dream project you’d love to reimagine next?

Absolutely. Honestly, I don’t think I’ve ever said this in an interview before, though I’ve told DC Comics many times over the past 15 years: I would love to work on Booster Gold. I just really love that character, and I think there’s so much potential to tell great stories with him.

On the Marvel side, there are a few, but the one that stands out is Iron Man. It’s interesting because Iron Man has become such a massive character in popular culture, and he’s become strongly associated with Robert Downey Jr.’s version—the wisecracking, motor-mouth persona. That was never exactly the comic version of the character, and it’s not the Iron Man that resonates most with me. The comic version hasn’t fully become RDJ, but it’s definitely been influenced by that portrayal.

Still, I’ve always wanted to write Iron Man, and I would love to, though I’d probably need to rethink the story I’d tell now, given how well-known and established he is.

What kind of major shift would you love to see in how the industry treats writers and artists?

I really appreciate this question. I’d break it into two parts.

First, when it comes to the industry, I wish creators were treated better in terms of compensation. I understand that comics aren’t a huge business and that sales have declined in recent years, but Marvel and DC are owned by multi-billion-dollar corporations. Their characters have generated literally billions of dollars, yet the people creating the stories behind them—especially the writers working today—often earn very little. For example, a comic that inspires a blockbuster movie like Iron Man or Black Widow can make hundreds of millions, while the writer of the comic might be making something like $12,000 a year. That’s an outrage. It’s how capitalism works, but there’s no real defensible reason for it. I’d like to see more of that movie money get funneled back to creators, both past and present.

Second, I think artists deserve more recognition. Since the ’80s and ’90s, writers have become the “superstars” of comics, but comics are fundamentally a visual medium. I’m a writer, so I’m not arguing against my own contributions, but the reality is that people would buy the art alone—without the story—because it has intrinsic value. Of course, the best comics succeed because of the combination of art and story, but too often artists are treated like hired help, especially by those outside the industry who see comics only as IP for Hollywood. That’s unfair, and it should change.

Finally, on one more point: No way, ever, if you use AI, you should not be involved in comic books. That’s what I’d say.