- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

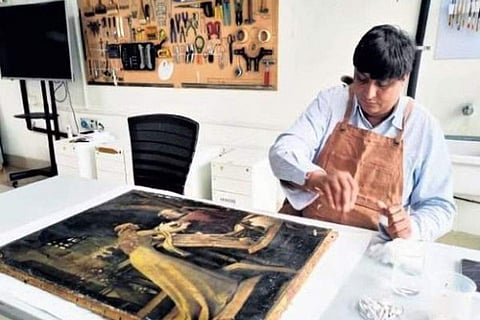

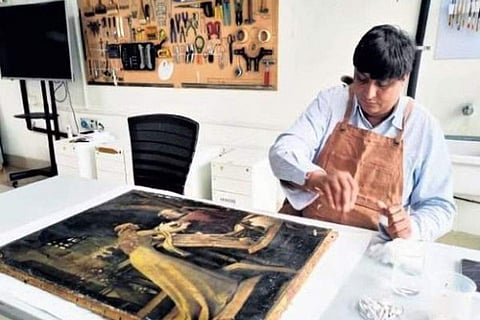

Canvases and stretchers propped up against walls and on large tables, four of which are placed strategically across the entire flat. At the centre of the space, two men in face masks sit hunched over an upturned painting covered with what looks like a plastic sheet held in place using weights. One is blowing air on it with a hair dryer, the other irons it, even as heady fumes fill the air. The manicured façade of art conservator Priya Khanna’s Art-Life Restoration Studio in Delhi’s Defence Colony belies the chaos within, much like how the now-flawless surface of a 60s’ painting, Mullah and Mariyam, by MF Husain hides the damages caused during the terror attack on Mumbai’s Taj Mahal Palace hotel in 2008.

The oil-on-canvas with a rich blue backdrop had developed an uneven patch due to discolouration along the vertical line of the painting. It ran through the male figure, which accompanies a white feminine form in Husain’s familiar bold lines on its left. “Water had been dripping behind the painting for some time. The ground layer of the canvas, which the artist prepares before starting to paint, got dissolved because of water absorption. It caused the paint to flake. So we first consolidated what was left of the work, then made strokes of fillers to patch the gaps, before retouching it,” says Khanna, whose team restored the hotel’s entire art collection of 200 pieces—paintings and paper works—in a span of nine months following the attacks. Khanna is part of India’s current art conservation brigade that is standing tall as the custodian of a heritage that would have otherwise withered away with the passage of time.

The beginnings

Contrary to what one would believe, conservation of art in India is a fairly recent phenomenon—about half a century old. Prior to that, the field was largely focused on the preservation of monuments. A defining moment in the field came with the appointment of artist Sukanta Basu as a conservator at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Delhi, in the 1960s, followed by the establishment of the National Research Laboratory for Conservation of Cultural Property (NRLC) by conservationist OP Agrawal in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture in Lucknow in 1976. “Basu and Agrawal introduced the idea of the conservation of art objects in India. The former was also sent to institutes in Italy and London where he learnt the restoration techniques,” says Rahul Tongaria, who leads the four-member conservation team at the NGMA. The gallery’s collection of modern and contemporary art comprises over 20,000 art objects across mediums, including paper, canvas, wood, stone, metal, glass among others.

Following a nearly decade-long stint at NRLC, Agrawal founded INTACH with cultural archivist Pupul Jaykar in 1984. It was, however, only with the establishment of the National Museum Institute of the History of Art, Conservation and Museology five years later in Delhi that the movement got a real boost. “It became the first centre for formal education and research, with programmes that aimed to provide in-depth technical knowledge and skills in the field,” says Satish Pandey, HoD, Conservation Department at NMI. Several leading conservators in the country today, including Khanna, Tongaria and Achal Pandya, who heads the Conservation Unit at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), Delhi, have received their education at NMI.

Under Pandya, the department, established in 2003, has been conducting the conservation of paintings on paper and canvas, tribal art, murals as well as books and manuscripts. The unit’s expertise was on display last year when the Nehru Memorial commissioned the restoration of a delicate painting gifted to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru by Vietnamese President Ho Chi Minh in 1958. The 40x35-inch soft painting on silk shows a one-pillar pagoda flanked by intricately drawn trees. Damages included fraying of the silk threads in the lower half of the painting and biological infestation. “We first exposed the back to get a better measure of the original craftsmanship. The entire frame was then protected with plexi-glass to prevent further ruin. It took about two months to complete the process,” Pandya says.

The Science of the Art

In conservation, necessity is the mother of invention. Across the NGMA lab, alongside the easel-mounted works, which are at different stages of restoration, are strewn smaller canvases with seemingly random strokes of paint or tiny patches of lining stuck together. “These are testers,” says Vipin Joshi, technical restorer at the gallery, adding, “You cannot directly jump into the treatment without being sure that your approach will not damage the work further.” It is only after several rounds of hit-and-trial that a conservator finally settles on a solution. They must, therefore, not just be familiar with the mediums of the artworks, but also the science that enables them to understand its compatibility with the restorative treatment.

For instance, while restoring a 19th-century Japanese bronze sculpture, the team at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai, used a combination of traditional and modern techniques. Part of the museum’s bequest that came in 1922, the piece took a year to be restored, recalls Nikhil Ramesh, who heads its conservation department. He adds, “We found that there was an overcoat of plaque on it. We used X-ray fluorescence to determine the elemental composition of the object to discover that there was gold and silver gilding on it. The cleaning was done using modern-day lasers as well as traditional solvents. We, however, decided not to clean the entire surface, but only certain parts to reveal the gold and silver underneath that enhances the aesthetics of the sculpture.”

Another challenging project undertaken by the NGMA was restoring a 1980 oil-on-canvas work, featuring a group of boatmen on the beach, by artist Upendra Maharathi. The damaged work—it had deposits of mud and soot, and two large holes—was part of the artist’s collection that was bequeathed to the gallery by his daughter a few years ago. “The stretcher too had been attacked by termites. It took us three hours daily for 25 days to restore the work,” says Tongaria.

The field is a blend of art and science—two disciplines that have traditionally been pitted against each other. That you can apply your skills from a degree in chemistry or physics to a painting, sculpture or photograph seems unimaginable, except that they are two pieces of a puzzle that perfectly fit together. The lack of awareness of the fact, however, makes it not the most obvious career choice for students in either field. No wonder then that most of the conservators practising today had stumbled upon the profession.

Manpower Matters

While art conservation in India has developed in the past five decades, it has a long way to go before catching up with the West. According to Pandey, the country is about a century behind. “Our museums were only established post-Independence, and many of them still do not have trained conservators,” he says, adding, “Most professionals have only been trained as part of an apprenticeship or have a course certificate (three-six months), which is insufficient.”

It was this gap that art conservator Anupam Sah was looking to fill when he joined as an academic consultant for the Art Conservation Initiative by Tata Trusts (between 2019-23) in collaboration with five partner institutes across India. These include Kolkata Institute of Art Conservation (manuscripts, miniature and oil paintings); Nainital-based Himalayan Society for Heritage and Art Conservation (stone and wooden objects and sculptures); Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru (paper works, including prints, drawings and maps); Mumbai’s CSMVS (natural history specimens, metals); and Mehrangarh Art Conservation Centre (wall paintings and textiles) in Jodhpur, Rajasthan.

Sah, who currently runs Anupam Heritage Lab in Nainital and Mumbai, where he also served as the head of the art conservation department at CSMVS from 2009 until March this year, says, “Lack of cultural heritage conservation was almost always linked to lack of government resources. But today, there are plenty of grants and schemes both in the government and private sector, such as Ministry of Culture schemes (the Scheme for Safeguarding the Intangible Heritage and Diverse Cultural Traditions of India, Museum Grant Scheme, Scheme of Financial Assistance for Promotion of Art and Culture) and growing CSR funding, which aim to promote and preserve art.” According to him, with adequate funding, the solution is to have a well-skilled conservation ecosystem, appropriate infrastructure, and a more inclusive and balanced theory- and practical-driven curriculum in the field. Under the Tata Trusts initiative, early- to mid-career, conservators were trained by the likes of Sah to get rigorous hands-on training.

The Emami gallery in Kolkata currently has on display a retrospective—Lalit Mohan Sen: An Enduring Legacy—of the lesser-known modernist, featuring drawings, photographs, prints and paintings created during his three-decade career between 1924 and 1954. Approximately 90 percent of the exhibited works were restored at Kolkata Centre for Creativity (KCC) by conservators, many of whom were trained under the initiative.

A lab staff member talks about a 20th-century oil painting featuring a portrait of a girl, which was originally created using the impasto technique on a compact-weave jute canvas. During inspection, it was found that the paint layer had fragmented and the canvas was stuck on a mount board with tape. “That the canvas was not stretched was also contributing to the instability of the paint layer,” the conservator says, adding that surface grime and natural ageing of the original pigments too were prominent. They first consolidated the paint layer, followed by further treatments, including addition of the lining, filling the cracks and retouching.

Looking Through the Lens

A tricky segment in the conservation of visual art is photography because the process of generating images has undergone several changes through history. It began with heliography, then came salt print, cyanotypes, albumen print, gelatine dry plate, film negatives, and finally colour photographs before the advent of digital cameras. “With oil painting, the base materials remain the same—canvas and paints. In photography, however, they differ depending on the process (for example, tintype used emulsion painted directly onto an iron plate, while gelatine silver print uses paper coated with an emulsion of silver halide in gelatine),” says Rajeev Choudhary, acting head of conservation at MAP. Among the oldest photographs in its collection are Felice Beato’s images of Lucknow from the 1857 revolt. They also have photographs by names such as Bourne & Shepherd, Lala Deen Dayal and Wilson Studio among others. To encourage conservation in the sub-field, the culture ministry in 2016 tied up with the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) with a fellowship programme that has an entire segment on photograph conservation. Choudhary and Ramesh have been fellows there.

Both, however, are only carrying forward the legacy of Pune-based S Girikumar, who is one of the first photograph conservators in India. Elaborating on why restoring photographs is difficult, he explains, “Most people treat photographs as any other print on paper, but there are different processes that can yield similar-looking images but behave differently under similar conditions. For instance, if there’s no damage to the emulsion or any fungal attack, a gelatine print can be treated with water. But in a similar-looking collodion print, the image-carrying layer crumbles the moment it comes in contact with water.”

A physics graduate, Girikumar was pursuing his masters in astrophysics when he switched streams to join the NMI course in 1988. Ask him what prompted the move, and he says, “I was simply choosing something I was interested in. At that point, it was artefacts.” Girikumar went on to train at the Conservation Laboratory of Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Italy, and then the Centre for Photographic Conservation in London. He worked with INTACH Conservation Centre in New Delhi for four years before starting his private practice about three decades ago.

Talking about the lack of efforts in photograph conservation, he says, “It isn’t considered a high form of art. The notion that photographs are mass-produced and can be copied indefinitely without any reduction in value has also led to not giving enough importance to their conservation.” They are nevertheless a testimony to the passage of time. “A photograph’s historical integrity is not just limited to its content, but also the process through which it was produced. Photography is proof of how far we have come,” Girikumar adds.

On Borrowed Tools

In conservation, precision is key, whether it is in putting fillers, sewing tears or treating a discoloured patch. It is also not very different from the medical field in execution. “We are like that one doctor in a village who is a general physician, gynaecologist, ENT specialist all wrapped into one,” says Ramesh. He insists that each member of his team of 30, who are responsible for the upkeep of 70,000 objects—including ancient artefacts, miniature paintings, decorative arts as well as European paintings—in the museum collection, knows the basics across all mediums.

The profession borrows more than just the analogy from the medical field. Almost all tools—steel micro spatulas, tweezers, awls, scalpels, cotton swabs and bone folders—have their primary use in the medical industry. Advancements in devices impacts conservation practices. For instance, as the image-reading moved from X-Ray to CT scan, it changed the documentation process in conservation. Infrared reflectography, which helps a physician to measure a person’s body temperature, allows a conservator to spot damages and previous restoration processes done on a work with more clarity.

The latter came in handy when Khanna was restoring an oil-on-canvas work from the 1900s that was completely painted over. Sah recalls working on a 1,500-year-old stucco sculpture of a seated crowned Buddha from Gandhara in Afghanistan during his time at CSMVS. “Lasers were used to cut centuries-old grime and dust to bring the two-feet-tall rare piece, quite literally, to light,” he says.

Notwithstanding the slow pace of art conservation, younger conservators continue to join the brigade. Manasvini, founder of the three-year-old Kadhir Conservation in Chennai, is one of them. She, along with her three-member core team, handles everything from consultation, condition analysis, indexing and periodic maintenance. The 30-year-old decided to start her own practice, after an internship at MAP, because “the conservation scene in Chennai was underwhelming”. One of Kadhir Conservation’s first large-scale projects was the conservation of the Lalgudi Trust collection (belonging to the family of renowned violinist Lalgudi Jayaraman) that comprised letters, notation books, posters, photo albums, diaries, awards and paintings. “Over the past year, we have categorised, indexed and conserved close to 2,200 objects,” Manasvini says. Even as India has a long way to go before it catches up with the West, with continued efforts from veterans and new entrants alike, its art restoration brigade is only getting stronger, one conservator at a time.

PREVENTION AND CURE

Two capacities in which art conservation is carried out Preventive Conservation: When one takes measures to prevent potential damage by controlling external factors such as protection from excessive light and a proper store with medium-appropriate temperature. The approach is taken on a larger scale that focuses on protecting entire collections rather than individual works of art. The objective here is to avoid any possibility for the requirement of treatment. For instance, ensuring compatible levels of moisture in the air using dehumidifiers while storing, say, a paper work, so that it does not develop acidity, which causes it to yellow. It is considered to be the most effective form of conservation as it reduces the need for individual treatments, subsequently decreasing the pressure on manpower and technological resources.

Curative Conservation: Also known as restoration, it is undertaken when the damage is done and an artwork is to be treated to return it to its original state as far as possible. This involves cleaning of dust, soot deposits, removal of varnish, reconstruction in case of flaking of paint and tear repairs. Not only is it more expensive, but also requires a superior knowhow of mediums, their chemical composition and reactionary traits. For instance, to recreate a patch of flaked paint layer, one has to first get the shade of the pigment that matches the original. Besides that, the elemental composition of the colour needs to be inert—it does not chemically react with the original paint layer—to prevent further deterioration. For this, test patches are made and often only after several rounds of hit-and-trial a conservator achieves the required result. Curative conservation also uses state-of-the-art equipment such as lasers, infrared reflectography, stereo microscopes, steel spatulas and vacuum mist machines.

FILL IN THE BLANKS

Problems to look for in different mediums

Oil painting: Tears, holes, loss of ground layer, cracking and flaking of paint, colour changes, attack by fungus, termites or silverfish, improper restoration and vandalism

Paper artworks: Getting stuck to the base, increased acidity causing the paper to yellow, tears, fungus, rust and water stains, tarnishing of dyes used

Photographs: Abrasion, fading of the image

and curling due to environmental factors such as temperature, humidity and pollution, yellowing

due to exposure to light, and sticking of photographs together

Sculptures: Deposition of rust in case of metal, breakage, rotting in case of wood due to exposure to water and humidity, soot deposits for stone sculptures in areas of

high pollution

Fresco: Flaking of paint, microbiological growth, disintegration of plaster, salt efflorescence, formation of paint blisters