- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

A contemporary installation brings Indian craft, mythology and self-reflection into the same physical space.

In Indian cosmology, the sun does not move alone. Surya’s chariot is drawn by seven horses, each carrying a force that sustains the world, from heat and light to rhythm and moral order. It is a familiar image, repeated across sculpture, painting and ritual. Ashvahit, a new large-scale installation by MeMeraki, returns to this idea without retelling it. Instead, it breaks the image apart and rebuilds it through living craft traditions, asking what the sun represents in the present tense.

Commissioned by India Exim Bank and unveiled in Mumbai, Ashvahit presents six sculptural horse faces and one absence. Each form is produced through a distinct regional craft, selected for the way its material and history align with a specific solar quality. The seventh horse is unseen. In its place, a mirror confronts the viewer with their own reflection.

Founder Yosha Gupta traces the project back to a wider moment of transition. “We wanted to explore the significance of the astrological shift from the year of Snake to the year of Sun, and the transition from Kali to Rudra,” she says. “This shift encourages us to shed our old selves and accept reality from within.” That inward turn shapes the entire installation, from the choice of crafts to the decision to leave one element invisible.

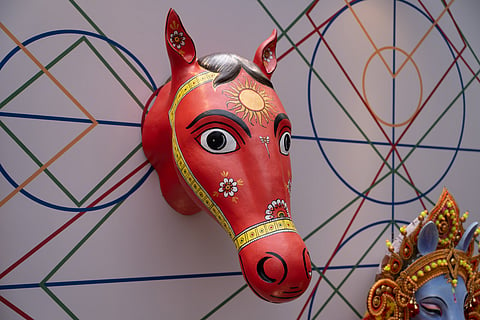

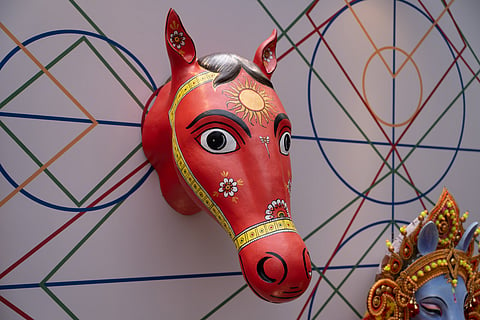

The six visible horses represent Energy, Illumination, Truth, Discipline, Joy and Harmony. Energy is carried through Cheriyal painting from Telangana, its red ground and graphic figures setting the pace. Kashmiri papier-mâché follows, handling light through surface and sheen. A Kushmandi wooden mask from West Bengal speaks to Truth through its severity, while Discipline is realised in Bastar metal from Chhattisgarh, firm and unyielding. Joy enters through Chhau masks from eastern India, carrying the trace of movement and performance. Harmony is shaped through a Majuli mask from Assam, informed by river life and seasonal change.

“For each value, we carefully matched it with a craft tradition that resonated with its character,” Gupta explains. “Each horse head represents a specific value, and we wanted the material language to carry that meaning.”

The artists involved come from different regions and lineages, yet the installation resists any sense of a survey. Each work stands on its own terms, while remaining part of a shared structure. The Cheriyal horse, created by artist Sai Kiran, demonstrates how that balance plays out in practice. Tasked with representing Energy, he found himself pushed beyond familiar methods. “I approached representing Energy by leveraging the bold and vibrant nature of Cheriyal art,” he says. “The project pushed me to experiment with new materials and techniques, like making a mask with clay and taking a fibre mould, which was a departure from my usual natural materials.”

That experimentation extended to colour and expression. The horse’s surface is saturated with orange-red tones, its eyes exaggerated and alert. The result feels charged rather than decorative. For Sai Kiran, the process opened new questions about material and form. He speaks about an emerging interest in alternative bio materials and their structural strength, a line of enquiry sparked directly by the demands of Ashvahit.

Although the artists worked separately, awareness of the wider project shaped individual decisions. “Seeing the visuals of other horse heads being made in different craft forms was inspiring,” Sai Kiran says. “It gave me a sense of cohesion and encouraged me to experiment within my own craft.” The knowledge that his work would sit alongside metal, wood and papier-mâché prompted him to push Cheriyal beyond its usual flat surface, towards something more sculptural and architectural.

The most striking gesture in Ashvahit is the seventh horse. Rather than attempting to visualise an inward force, MeMeraki chose to leave it unmade. The mirror stands at the centre of the installation, quietly shifting the work’s focus. “The seventh horse represents the inward principle, guiding viewers to look within themselves,” Gupta says. “The mirror serves as a reminder that the answers lie within.” In a room filled with crafted objects, the reflective surface feels deliberately exposed, implicating the viewer in the narrative.

Ashvahit sits within MeMeraki’s wider practice as a culture-tech platform working to support traditional artists at scale. Founded in 2019, the organisation has built a network of more than 500 master artisans, documented hundreds of art forms and paid out over ₹7 crore directly to artists. Its work moves between education, commerce and research, using digital tools to bring practices shaped by local markets into wider circulation.

Ashvahit signals a different register. “Ashvahit resonates with modern India, particularly the youth, who are breaking free from traditional norms and seeking to understand and express their own truths,” Gupta says. “The themes of self-discovery and transformation speak to contemporary concerns.” Craft is treated less as something to be safeguarded and more as a working language, able to speak to present-day experience.

The decision to frame 2026 symbolically as the Year of the Sun gives Ashvahit an open-ended quality. It does not resolve its own questions. The horses remain fragments, the seventh permanently deferred. What holds the work together is the viewer’s movement through it, from object to object and finally to their own reflection.

In that final encounter, Ashvahit becomes less about Surya’s journey across the sky and more about how ancient ideas continue to circulate through bodies, materials and choices. The sun, here, is not distant or monumental. It is something assembled by many hands, shaped by regional knowledge, and completed only when someone steps close enough to see themselves within it.

For more updates, join/follow our WhatsApp, Telegram and YouTube channels.