- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

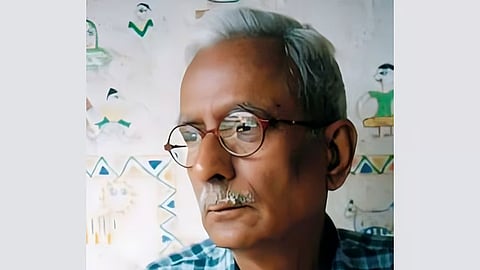

Widely regarded as a major Hindi writer, Vinod Kumar Shukla gets the Jnanpith award at the age of 88. His early poems, which made him appear as an ‘odd’ poet, were written in the late 1950s and the early ’60s, and it has been a writerly career running into nearly 65 years.

All along, his locus has been everyday life, and his focus, the utterly ordinary. His creative imagination very early decided to be entirely concerned with the ordinary without any trapping of myth or history. In him, in a way the century-long creative efforts in Hindi to put the ordinary man, the everyday life at the centre of literary imagination, gets a powerful articulation. It is amazing that for decades he has been exploring the dilemmas, the ironies, the charm, the dignity, the despair, and the disappointments of the ordinary with deep empathy, unusual understanding and audacious assertion. He has been, to borrow the title of the book of translation of his poems into English by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, ‘Treasurer of Piggy Banks’. And yet, his universe of everyday life is not dull or boring: on the contrary, it is a universe which reveals the irrepressible humanity, its humorous aspects, warmth and irony.

Vinod’s imagination and creativity are centered on the small-town ethos, neither rural nor cosmopolitan. His poetics is that of silence, reluctance and reticence. It scrupulously avoids hyperbole, heroics, and theatrics. It is difficult to find another Indian writer who has made ‘anayak’, the non-hero, his lifelong protagonist as Vinod has. The seemingly tranquil and humdrum reality in his writing, all too often conceals some disturbing unanticipated truth. And yet, here is a writer who has very seldom talked or written about his own work, neither clarifying some aspects nor articulating his vision in intellectual terms. He has hardly ever intervened in the furious ideological debates and controversies which have been at the centre stage in the literary world. He has not cared to clarify his ideological stand nor tried to justify his work. A ‘defenceless’ writer, he has been attacked as being a formalist, unconcerned with the socio-political upheavals in his native region of Chhattisgarh. This in utter disregard of the fact that a large section of his poetry, especially in his later life, could be read as a lament for and outrage at the plight of the Adivasis. In a deeply organic sense, he has been a writer of life as he lived and found it both in his home and family, and next door. A writer who can be seen, all too often, as a neighbour, concerned, disturbed and moved by what keeps happening to us humans in the neighborhood. And, by the same token, for him the cosmic and the domestic keep on coalescing into each other.

Vinod Kumar Shukla attained his own distinct voice in poetry and fiction, almost, in his first books of poetry and fiction. He ever so gently deviated from the conventional grammatical syntax to make his language more accommodative, to embody the surreality, as it were, of normal life. This quiet deviation has been an essential element of both his poetics and narratology. Even the titles of his first three books, two of poetry and the third his first novel, exemplify this device: ‘Lagbhag Jai Hind’ (Hail India, Almost), ‘Vuh Aadmi Naya Garam Coat Pahin Kur Chala Gaya Vichar Ki Tarah’ (That Man Put on a New Woolen Coat and Went Away Like a Thought) and ‘Naukar Ki Kameez’ (The Servant’s Shirt). Some lines of a poem written in 1976 could be recalled in Arvind K Mehrotra’s English version:

When the bus arrived

I waited for the tree to get on first when it struck me

that trees

Do not board buses.

And lines from a recent poem are:

My movements are/so slow/ that even a small house/ seems large

Never far from each other/ we look for each other/ and find each other/ right here.

One of his later novels is entitled ‘Deewar Me Ek Khirki Rahati Thi’ (A Window Lived in the Wall). He has, far more than half a century, retained a sense of existential mystery and wonder. As a writer, he keeps on reminding us that there is a lot in our everydayness which deserves attention and that our humanness, all too often, resides in small things, in seemingly trivial details of our unexciting life. He also, in a way, walks with us reaffirming our inevitable companionship.

I extend my hand.

He held my hand and stood up.

He did not know me

but he knew my hand.

We walked side by side.

We did not know each other

but we knew how to walk together.

This article is written by Ashok Vajpeyi