- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

True crime no longer lurks in the shadows. It lives in our feeds, our playlists and our small talk. On a day like Friday the 13th, the obsession almost feels poetic.

We used to whisper about murder. Now, we binge it over brunch.

Once confined to yellowing newspapers and late-night local news, true crime has exploded into our lives in high definition. What played out behind courtroom doors and lay buried in police files is now re-imagined in podcasts, documentaries and bestselling books. Murder and mystery don’t just entertain us — it warps our fears, rewires our empathy and blurs facts with feelings.

True crime is far from new. Police officer Priyanath Mukhopadhyay’s writings in Bengali periodical Anusandhaan (1889), based on real police cases, are considered some of the earliest true crime narratives in Indian literature, decades before Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood in the 1960s popularised the genre in the West. However, something changed in the 21st century. When Serial premiered in 2014, it didn’t just recount a murder — it framed the story like a detective novel, inviting listeners to solve it with the host. Since then, true crime podcasts have flourished, drawing millions of loyal fans. On screen, shows like Indian Predator have turned real criminals into viral characters and dinner–table debates.

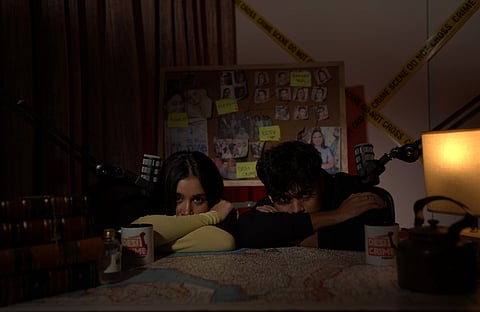

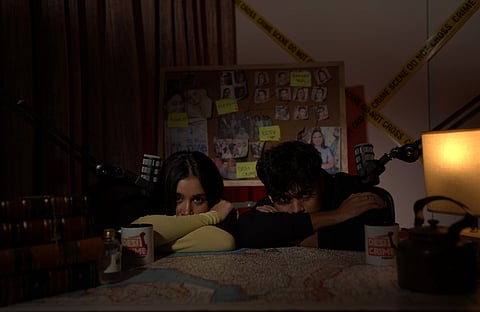

In a genre long dominated by Western voices and white stories, The Desi Crime Podcast cracked open a door. Aishwarya Singh and Aryaan Misra didn’t have a studio or a team. Just a dorm, some mics and a question: why do all these crimes sound so... white?

“We were just two college kids,” Aishwarya says. “Twenty years old, sitting in our dorm room one night, when it hit us. There was nothing out there representing Indian or South Asian cases in podcasting.”

Aryaan didn’t even care about true crime. But he asked the right question: “Why are you only listening to podcasts about white crimes?”

That moment of casual frustration turned into a mission. With laptops and a sense of absence, they began telling stories that felt like their own.

Some storytellers don’t just tell the tale. Some are staring into the dark — and daring us to look too.

Filmmaker Patrick Graham, for instance, isn’t lured by shock value.

His documentary on Shakereh Khaleeli (Dancing on the Grave) isn’t just a retelling, it’s about how society allows certain women to vanish unnoticed.

They aren’t just stories. They’re systems. And sometimes, the scariest monsters aren’t killers — they’re norms.

Author Anirban Bhattacharyya sees the roots of obsession in childhood.

His first attempt at writing crime? Age eleven. A handwritten book titled The Adventurous Six: The Sinister Summer Holiday that got published decades later.

There’s strange poetry to that — a child drawn to danger, a man still writing his way through it.

True crime, she says, is a way to flirt with fear without consequence.

“There is such a thing as healthy morbid curiosity,” she insists. “It’s okay to be curious about crime — what matters is whether it’s becoming an obsession.”

For Aryaan, the hook isn’t gore — it’s structure. “Who did it? Why did they do it? What really happened? These are questions that naturally drive the narrative forward.”

But he knows who’s tuning in. Women.

Aishwarya offers a sharp comparison, “Think about war films. Men tend to relate more because of social conditioning and a sense of imagined experience—adrenaline, brotherhood. True crime works the same way, but for women.”

Dr. Rachel agrees. “Women are generally more drawn to crime thrillers across formats. They’re naturally more attuned, even biologically, to experience empathy and compassion. That emotional engagement — especially with the victims and their families — is a big part of why these stories resonate so strongly.”

“People are excited by violence,” Patrick says. “They like to see horrific stories from the comfort of their own homes. It’s slightly about, ‘Look what happened to that person — I’m so glad it didn’t happen to me.’ "

We don’t just watch violence, we measure ourselves against it. We survive by comparison.

“People have always been drawn to these stories,” Aryaan says. “The obsession existed even in the 17th century. We’ve just swapped newspapers and radio for Netflix and Spotify.”

But fascination isn’t the same as innocence.

Dr. Rachel calls it “the kind of darkness we find compelling.” A safe way to feel danger. A dose of horror we can control.

But for the people who makes this content, the horror doesn’t always turn off with the mic.

Patrick uses emotion as a compass. “When I get angry, I know I’ve found the story’s heart,” he says. But when it’s over? “I move on. I’ve learned from it. But I don’t let it stay.”

Anirban doesn’t get to walk away. “It’s always a struggle. Sometimes I’m physically sick. Writing about child murders or violent crimes is draining; it's like an out-of-body experience where I channel the killer or victim. But I feel a moral responsibility to tell these stories. True crime deserves more respect. It’s not just pulp: it takes you where no one dares to go.”

And maybe that’s what keeps us listening. Not just the shock. But the meaning.

Today, true crime is no longer niche. It’s mainstream. We dissect it. We stream it. We turn it into content, into conversation, into art.

It’s not just entertainment — it’s how we try to understand ourselves.

And for better or worse, we can’t seem to look away.