- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

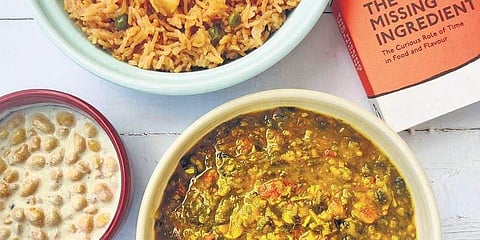

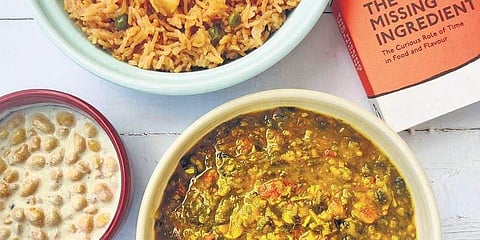

A Bunt family (a community that traditionally inhabits the coastal districts of Karnataka) tried out the quintessential Sindhi breakfast of Dal Pakwan for the very first time during the Covid lockdown. Chana dal commonly served with raw onions, spicy mint chutney and sweet and tangy tamarind-date chutney to be scooped with crunchy fried bread... this and other such delicacies from various cuisines became a part of any city’s cultural fabric.

“People were curious at first and I am happy to report that I have got a great response for Sindhi food from Bangaloreans,” says Kusum Rohra from Mumbai, who now calls Bengaluru her home. After the pandemic struck, she started her home food venture called Khado by Kusum via Instagram and it continues to bring her business. She eventually registered with Airmenus because it streamlines communication and payments, saving her time and effort.

Globally, women’s jobs are 1.8 times more vulnerable to the Covid crisis than those of men, according to a July 2020 report by the McKinsey Global Institute. However, a less pronounced collateral benefit is that the pandemic got respect for remote work and for women this has been a mixed blessing. One can attribute this shift in trend to the arrival of food aggregator platforms for home chefs such as HomeFoodi, Foodcloud and other smaller city-centric ventures that help connect small-batch home food makers to consumers. The aim of these aggregators is discovering different cuisines, home pantries and to give a chance to familiarise yourself with foods from different regions. Rohra has moved from weekend deliveries to delivering every day. She is catering to intimate gatherings also. Industry experts feel just as demonetisation paved way for fintech and the digital economy, the pandemic facilitated food tech and home food concepts.

Narendra Dahiya, the founder and CEO of Homefoodi, has been able to expand from Noida to Ghaziabad, Delhi, Bengaluru, Mumbai and Hyderabad within two years of their launch in November 2019. Most of their associates are also women who are earning for the very first time. “Even the government is excited about this opportunity and has legalised home chefs. It’s a big endorsement as they face fewer issues from their respective RWAs.” In a city like Delhi, a thali costs about `120. A chef who has built a loyal customer base over time does an average of eight to 10 orders a day and can make up to a lakh per month. The marriage and motherhood penalty still exist. Dahiya adds, “Our research told us that most of the homemakers were at home because of their circumstances and not by choice. The most convenient way for them to earn a living was to sell homemade food. NRAI also confirms that the home chef segment is the fastest growing in India today.”

Aparna Nadig from Bengaluru started Rasa and Co with her mother Anasuya Nadig during the lockdown. “It started as a passion project to supply healthy, wholesome South Indian food to friends and family who live alone. We supply vangibath powder, chutney podis, pickles, rasam-sambhar powders and more of the regular staples. On special occasions, like Sankranti, we made Yellu Bella, a trail mix of sorts and Sakkare Acchu, sugar candies moulded in various shapes and other lesser-known dishes.” They hired a single mother for help and hope to employ more women.

In Surat, Satyen Naik, Founder, Kitchen GJ05 - Ghar se Ghar tak, observed that most of the chatter on social media during the pandemic was about food. He quickly launched Kitchen G0J5 to connect the city of Surat to its home chefs. Starting in June 2020, it now has more than 60 women home chefs, some of whom are the main income earners for their families.

Chef Suman Puri, 56, is fondly called Aunty in Surat. “I get calls saying, ‘aunty I want one parantha or a plate of poha for breakfast before leaving for work.’ I charge Rs 20 for a parantha with curd and Rs 35 for poha. I am glad I chanced upon Kitchen GJ05. My husband passed away just before the pandemic and I am a single mother. I am able to pay my rent and run my house with this food business.” Naik not only makes sure that hygiene, packaging and communication are of top quality, he also trains home chefs and helps promote them via his social media efforts. “During Ganesh Chaturthi, laddoos move faster. Foods such as sarson ka saag, and Undhiyu are ordered most in winters.”

As the world rebuilds itself post-Covid lockdowns, it remains to be seen if we can sustain these benefits.