- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

At 16, when Ganesh Shivaswamy first came across a Ravi Varma painting, little did he know that this would lead to a life-long bond. The vibrancy in colours of the chromolithographs appealed to him so much that ever since, the way he looks at the chromolithographs is very different from the way others look at them. He begins, “I say this because I absorb the colours, they fascinate me.”

A lawyer and academic, Ganesh is going to be in the city to deliver a talk on Music and Dance in the Raja Ravi Varma Oeuvre.

Hailing from Bengaluru, Ganesh has been collecting chromolithographs from the Ravi Varma Press, and now has quite a substantial collection. “Somewhere in 2018, I decided I have to give this collection a meaning, and I embarked on writing a book. What I instantly took into consideration was — is there anything new to be said about Raja Ravi Varma? I began my research and realised there is this whole segment that no one has actually tapped into — on how people engaged with the imagery; not the aristocrats or the royals which have been so extensively written about, but the common man,” shares Ganesh.

Also read: ‘Trans’cending boundaries

Titled Raja Ravi Varma — An Everlasting Imprint, the book is likely to be released in 2023. “I try to look at Ravi Varma not in isolation — something that others have done in the past. Rather, I am interested in what Ravi Varma was looking at when he composed an image. So, you see, the image is put into a larger context. Broadly speaking, it is an analysis of a journey of the image. I went to the Kilimanoor Palace, the Ravi Varma Press, I explored the archives — there’s just so much of research gone into it. So, I put all that in context to bring you stories behind these photographs,” he says, adding, “While we have been celebrating the artist, we have ignored the models, the influences behind each of his pictures. For instance, you are looking at a generic picture of a Krishna and Radha dancing painted by Ravi Varma, but who are they?”

So, what can people expect at the talk, we ask, and he says, “I want to have a conversation around only the music and dance aspect of this large canvas of work.”

Telling us more, Ganesh picks this particular picture of a model playing a sitar. “She is Rajibai Mulgaonkar, who was a Goan kalavant. Kalavants are like devadasis — women dedicated to art. These Goan kalavants usually made their way into Bombay, and Rajibai Mulgaonkar became the mistress of a very rich Bombay-based businessman. She modelled for Ravi Varma; the reason I know who she is, is because Ravi Varma has himself written ‘Rajibai from Bombay’ at the bottom of the picture,” he says, adding, “A very interesting angle that will come out in my talk at the event is that these were brave women. Imagine what it would have been like to pose for an artist in the late 19th century! It wasn’t easy, but these women didn’t care! Yet, we have not spoken about her in 130 years! That’s a lot of injustice we have done to her!”

Rajibai Mulgaonkar is the same girl who posed for the iconic Lakshmi painting — a girl standing on a lotus with four hands.

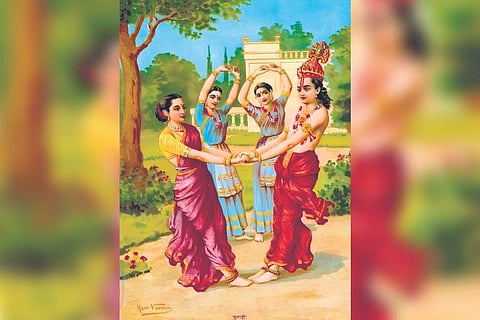

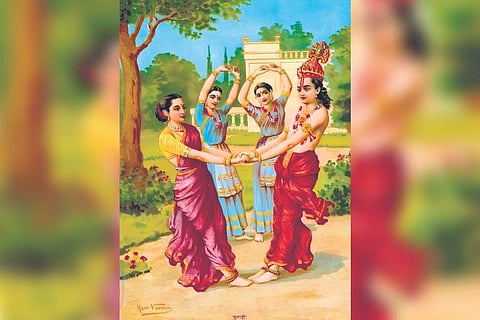

Giving us another example, Ganesh speaks about the painting of Krishna and Radha. “It’s a small chromolithograph, so heavily overlooked with most saying it’s an incongruous lithograph. On the contrary, it actually encapsulates a very interesting tradition — the Baroda bharatnatyam tradition. When Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III got married, his first wife Maharani Chinnabai I was from Thanjavur, and as part of the bridal entourage, there were two dancers who went with her from Thanjavur as a part of dowry. These girls then became the Baroda nautch girls. But, they were very highly qualified bharatnatyam dancers. When Maharani Chinnabai died, these girls didn’t know what to do. The Maharaja, a very practical man, had already created something called the Kalavant Kharkhana, a department of arts. He told the girls to be a part of the department, where they were paid really well — ₹430 per month.They were asked to dance before the Maharaja on Wednesdays and Saturdays. But when these girls performed before the Maharaja, he understood nothing as he didn’t know bharatnatyam! These two girls then decided to re-choreograph a few sequences just so the Maharaja, their patron, appreciates the dance. They redo a certain set of sequences which Ravi Varma happens to watch, and is fascinated, to say the least. He then sketches them as Radha and Krishna and that becomes this chromolithograph encapsulating a completely rare bharatnatyam tradition in Baroda. Look at the history!”

Ravi Varma loved kathakali and its influences are heavily reflected on his works. “Ravi Varma was a dancer himself and dabbled in kathakali. In fact, the Kilimaroon Palace where he hails from is famous for giving us visual artists. It had a number of people who wrote kathakali plays; Ravi Varma’s own mother wrote a script for a dance play called Parvati Swayamvaram. The palace interestingly also had a particular area called the Natakashala where they enacted kathakali plays. “So growing up, kathakali played a huge role in his life. A lot of facial expressions you see in Ravi Varma’s art is inspired by kathakali. People say Ravi Varma was very European; there’s no denying that, but the Indian influence is more dominant in his works.”

Ganesh says the audience can expect all this and more when he comes to Chennai for the event. “I have divided my talk into three segments — kathakali, music and bharatnatyam, and I will be talking at length on all that we ignore behind the great works of the artist.”

December 28.4.30 pm.

At Apparao Galleries,

Nungambakkam. Entry free.

—Rupam Jain

rupam@newindianexpress

@rupsjain