- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

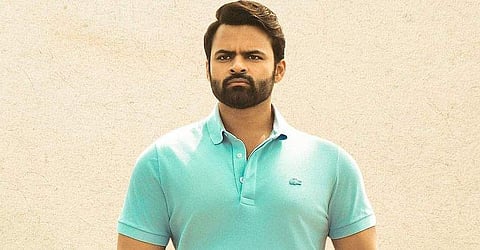

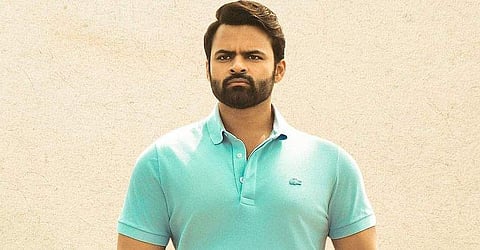

Republic opens with Abhiram (Sai Tej) driving through a narrow road in the rural premises of Eluru on a rainy night. We hear the Ilaiyaraaja composition, ‘Nammaku nammaku ee reyi ni’ from Rudhraveena in the background. He gets out of the vehicle to clear a branch blocking his way and notices a horde of men carrying weapons approach him. This ambiguous opening drops us in the middle of proceedings and the screenplay immediately shifts to the beginning. However, by the end of the film, when the opening scene appears in chronological order, the lines from the song, translating to ‘don’t trust the night’, radiate a haunting effect. The usage of the song serves as a red flag, but we don’t see it coming because the screenplay by Dev Katta and Kiran Jay Kumar keeps throwing surprises one seldom expects from a Telugu mainstream film.

Starring: Sai Tej, Aishwarya Rajesh, Ramya Krishnan, Jagapathi Babu

Directed by: Dev Katta

The story has a rather generic start point that reminded me of Vijay’s Sarkar. When Abhiram learns that his vote has been rigged, the authorities turn his back on him and the mishap that ensues seals his distrust in the corrupted ‘system’. The studious Abhiram, having cleared his UPSC exam, has to make a choice about whether he wants to pursue studies in the USA or crack the IAS interview and do his part to reform the society. Do I need to say which option he uses?

This could have been an underdog story chronicling the rise of the protagonist, but Dev Katta has other ideas. A character calls Abhiram “an experiment,” and this could be said of the film as well. Republic is not about Abhiram; he’s just a navigating device employed by the screenplay to expose the dark depths of the corrupted system the film tries to illustrate. Now, what does the system mean, you may ask. The writing personifies the system Abhiram wages a war against: The legislative body (politicians), the executive body (government officials like himself), and the judiciary system (a court, where the climax is set in). In fact, the closest Republic has to an antagonist is the corrupt minister, Vishakha Vani (Ramya Krishnan), but she’s not the most formidable villain either; she is simply a representative of corruption. The bigger villain here is the system itself, a point the film fascinatingly makes again and again.

Republic is a smart construction on the idea of corruption and how its repercussions seep into the lives of innocents. Take, for instance, the lady in the polling booth Abhiram interacts with early in the film. She propagates something that has been widely addressed in several films before—the problem of voters accepting money during election campaigns—but here, it adds to the film’s point that common people are complicit in the contamination of the system. This scene serves as a building block to the bigger statement the film makes towards its ending.

The writing is strong and coherent, and often goes beyond the obvious. Jagapathi Babu, who plays Abhiram’s father, is named Dasarath, and gets a fully fleshed character arc that not only adds to the film’s political angle but also brings immense emotional depth to the father-son angle. Vishaka Vani too, despite being a true-blue villain, is never stereotyped as the female villain. In fact, in a film that hardly tries to appease the fans with ‘hero’ moments, it’s worthy to note that it is Ramya Krishna’s character who gets two glorious ‘masala’ moments. Even when she draws an analogy between Charles Darwin’s Evolution theory and the voting demography, it doesn’t feel ostentatious because she is written really well. Furthermore, the screenplay restrains itself from pandering to the crowd though having many opportunities to do so. A notable character is killed in front of Abhiram, and you expect an action sequence, but we don’t get one. The film never takes the easy route.

Republic is a cynical portrait of the system that controls us and the inspirations from Alan J Pakula’s The Parallax View are evident, both in ideology and cynicism. The conflict, for instance, in both films, encircles a water body and mysterious disappearances. Like Joseph Frady, the protagonist of the 1974 film, Abhiram too finds himself in the thick of a mystery. The deeper Abhiram digs, the dirtier it gets. The Telugu film, of course, is more dramatic and Abhiram, unlike Frady, is an insider. But they both remain equally helpless in front of the big guns and are stripped off their powers in more than one instance. Visually too, the shot of the judicial committee Abhiram faces in the pre-climax is similar to the image of the judge’s desk from the Pakula film. The ending of the Dev Katta directorial, too, punctuates that there is no light at the end of the tunnel.

Even beyond its politics, Republic is a well-crafted film. I particularly liked the sequence in which Abhiram revises his IAS fundamentals, and how juxtaposing visuals of democracy keep getting cut between it. Sai Tej essays Abhiram with all the angst, but never goes overboard. His best performance comes during the interview scene, where he beautifully conveys both helplessness and anger. The ideas Republic communicates may seem familiar; its politics and emotional beats are not novel either. But a mainstream film is seldom this sincere and committed to its politics, and this makes the film a terrific return to form for Dev Katta.