- LIFESTYLE

- FASHION

- FOOD

- ENTERTAINMENT

- EVENTS

- CULTURE

- VIDEOS

- WEB STORIES

- GALLERIES

- GADGETS

- CAR & BIKE

- SOCIETY

- TRAVEL

- NORTH EAST

- INDULGE CONNECT

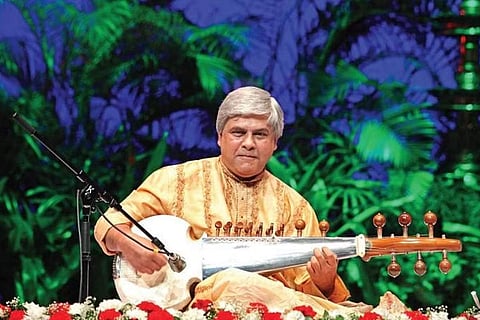

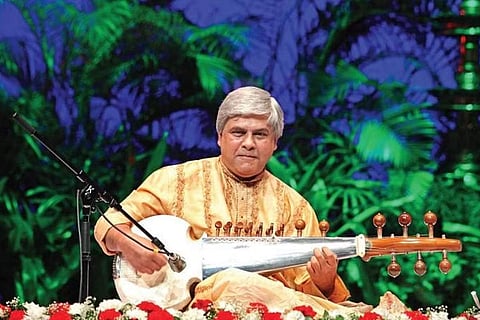

Sarod maestro Biswajit Roy Chowdhury recalls his father Ranjit Roy Chowdhury being annoyed with him when he was a child. Ranjit was a chemistry teacher who was also a sarod player. Five-year-old Biswajit would often sneak into his father’s room when he was away and pluck on the strings of the sarod, trying to recreate the music. “My father didn’t like anybody fooling around with his sarod, which he considered sacred,” says the 67-year-old adding that he understands the sentiment today: “You touch the sarod only if you intend to learn how to play it.”

Biswajit recently performed at Shriram Shankarlal Music Festival in Delhi, an event he has participated in over 10 times to date. The outdoor stage was festooned with garlands—it was opening after three years since the pandemic after an uninterrupted season of seven decades. Biswajit’s was the final performance. He enthralled the audience with renderings of maru bihag—a night raga which was appropriate for the occasion—and bandishes in vilambit, madhya and dhrut layas. Wearing his trademark chikan kurta (it was his sartorially impeccable guru Ustad Amjad Ali Khan who taught him about kurtas), he reminisces,

“One would think after the long run I’ve had, I’d be ready to hang up my boots, but I’m excited as ever,” says Biswajit, whose music is a combination of the Maihar and Gwalior gharanas. Amjad Ali Khan represents the sixth generation of the Senia Bangash gharana while his other guru Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur taught him the art of singing khayals (gayaki). In spite of, or perhaps because of the amalgamation of musical lineage, Biswajit’s style has a soul of its own. Skilfully extracting the sarod’s essence in tantrakari style, it becomes clear as the raga moves towards its climax that Biswajit can demonstrate an individual interpretation of the melody with improvisations in taan, resulting in a unique elucidation of cadences. The month of shravan (July-August), which marks the beginning of the varsha ritu (monsoon), holds a special place in his heart. “There is an endless variety of emotions, sensitivities and moods to be explored through ragas like megh malhar,” he says.

Biswajit has performed at prestigious concerts such as the Tansen Festival in Gwalior, the Sankat Mochan Music Festival in Varanasi and the Vishnu Digambar Jayanti in Delhi. In each one of them, he seems to balance the rules and conceptual freedom. “Internal paradoxes are what makes classical music unique. For example, in Amjad Ali Khanji’s renditions, orthodoxy coexists with spontaneity,” says the musician, who was brought to Delhi from Kolkata in 1978 by his guru. He recalls the first time he met Mansur. “Khanji sent me to pick him up from the railway station. I had lots of questions for him. Immediately after meeting him I asked him about the difference between raga gauri and priya dhanashri. Mansurji sat down right on the railway platform in the middle of the heat, noise and dust of Delhi, and began explaining the difference,” Biswajit laughs fondly at the memory.

He believes that the audience for classical music is diminishing not because of its complexity, but an overexposure to Bollywood songs. “Earlier, you’d wait for the five or six baithaks that happen every year. But today, people are waking up to Bollywood ringtones,” he says. As far as Biswajit is concerned, the sarod was the first musical sound he produced and hopes would also be the last.

Manan Bhardwaj's new single Never Together ft. Yesha Sagar releases

Fans bask in Linkin Park's ‘Meteora’ nostalgia as band unveils unreleased single

'I feel blessed and grateful,' British singer-songwriter RIKA on being signed by Warner Music India

Sharmi Surianarain wrote her way out of grief after losing her dad in her deeply personal EP 'Lost'